The Elusive Quest for a Universal Flu Vaccine: Progress and Challenges

For decades, scientists have pursued a universal flu vaccine that could provide broad, long-lasting protection against multiple influenza strains, eliminating the need for annual shots. Current flu vaccines are only 40-60% effective due to the virus's rapid mutation through antigenic drift. Researchers are now exploring innovative approaches targeting less mutable parts of the virus, including the haemagglutinin stalk, conserved epitopes, and internal structural proteins. While promising advances have emerged from multiple research fronts, significant challenges remain in developing a truly universal solution that could transform global public health.

The annual flu shot has become a familiar ritual for millions worldwide, but its effectiveness varies dramatically from year to year—sometimes dropping as low as 6% when vaccine strains don't match circulating viruses. This unpredictability stems from influenza's remarkable ability to mutate through a process called antigenic drift, where gene changes allow the virus to evolve away from vaccine protection. The quest for a universal flu vaccine represents one of modern medicine's most significant challenges, promising to eliminate the need for twice-yearly strain predictions by the World Health Organization and annual vaccinations. While the goal remains elusive, recent scientific advances suggest we may be closer than ever to achieving broader, longer-lasting protection against influenza's ever-changing threats.

The Problem with Current Flu Vaccines

Traditional influenza vaccines face fundamental limitations due to the virus's evolutionary strategies. Each year, global health authorities must predict which strains will dominate the upcoming flu season—a process that sometimes fails spectacularly, as occurred in 2014 when a mismatched vaccine provided only 6% protection. Even successful predictions yield vaccines that typically reduce infection risk by just 40-60%. The core issue lies in the immune system's natural focus on the haemagglutinin head—a protein on the virus surface that mutates rapidly, allowing influenza to escape antibody recognition. This biological arms race necessitates constant vaccine updates and annual administration, creating logistical challenges and leaving populations vulnerable during manufacturing delays or prediction errors.

Innovative Approaches to Universal Protection

Researchers are pursuing multiple strategies to overcome influenza's evolutionary advantages, each targeting different aspects of viral biology and immune response. These approaches represent paradigm shifts in vaccine design, moving beyond traditional strain-matching toward more fundamental immunological solutions.

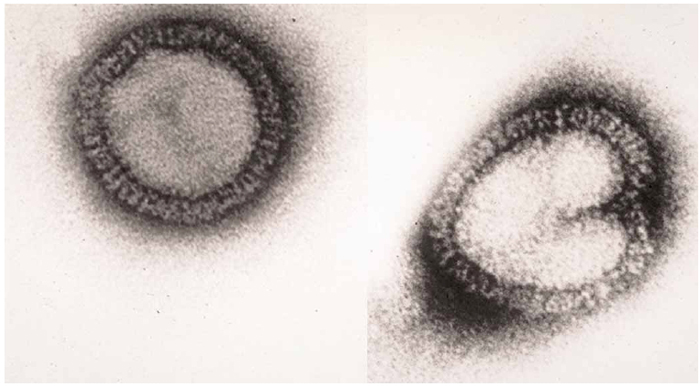

Targeting the Haemagglutinin Stalk

One promising approach focuses on the haemagglutinin stalk—the less variable portion of the surface protein that the immune system typically ignores in favor of the rapidly mutating head. Vaccinologist Florian Krammer and his team at Mount Sinai have developed chimaeric proteins combining familiar stalks with exotic heads, tricking the immune system into strengthening its response to the conserved stalk region. Since the stalk plays a crucial role in viral fusion with host cells and cannot mutate significantly without losing function, immunity against this region provides broader protection across strains. Early phase I trials showed this approach successfully induced stalk-targeting antibodies, though research was temporarily delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Computational Antigen Design

At the Cleveland Clinic, Ted Ross and his team employ computational modeling through their COBRA (Computationally Optimized Broadly Reactive Antigen) system to identify viral sequences that remain stable across evolutionary time. By analyzing thousands of sequenced flu genomes from humans and animals, they identify conserved epitopes that make promising vaccine targets. Their method uses historical data to predict future viral evolution, essentially allowing the virus's own evolutionary patterns to guide vaccine design. In animal studies, vaccines designed using only pre-2009 data successfully protected against strains that emerged years later, demonstrating the potential of this predictive approach.

T-Cell Based Strategies

Jonah Sacha at Oregon Health & Science University is pioneering a radically different approach focusing on T-cell immunity rather than antibodies. His team inserts genes for highly conserved internal viral proteins—matrix protein M1, nucleocapsid protein, and polymerase PB1—into a cytomegalovirus vector. These internal proteins cannot mutate significantly without destroying viral function, making them stable targets. In dramatic experiments, macaques vaccinated with proteins from the 1918 pandemic virus survived exposure to deadly H5N1 bird flu, while unvaccinated animals died within days. This suggests T-cell immunity could provide cross-protection against strains separated by a century of evolution.

Practical Realities and Future Prospects

Despite exciting advances, researchers caution that a truly "universal" flu vaccine may remain an aspirational goal. Nicholas Heaton of Duke University notes that even a vaccine ten times better than current options—potentially saving millions of lives annually—wouldn't achieve true universality. More realistic objectives include vaccines providing three to five years of protection before requiring updates, which would still represent a monumental improvement over current annual requirements. Such vaccines would allow year-round manufacturing, reduce costs, and improve global vaccine access. The U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases supports this research through its Collaborative Influenza Vaccine Innovation Centers (CIVICs) program, though researchers express concern about political interference and funding stability given recent administrative changes affecting vaccine research priorities.

Conclusion: A Game-Changer Within Reach

The pursuit of a universal flu vaccine represents one of the most important frontiers in preventive medicine. While challenges remain—including scientific hurdles, manufacturing complexities, and political uncertainties—the convergence of multiple innovative approaches suggests transformative progress is possible. Researchers agree that the most effective solution will likely combine multiple strategies, engaging both antibody and T-cell responses against both surface and internal viral targets. Even incremental improvements could dramatically reduce influenza's global burden, which causes millions of severe illnesses and hundreds of thousands of deaths annually. As Florian Krammer notes, a vaccine requiring only a few shots during a lifetime would indeed be a game-changer, bringing us closer to ending the annual battle against influenza's evolutionary ingenuity.