Animal Health Surveillance: A Critical Defense Against Future Pandemics

The 2024 H5N1 outbreak in US dairy cattle, first detected through unusual animal deaths, highlights the critical role of animal health monitoring in pandemic prevention. This article explores how the One Health approach—recognizing the interconnectedness of human, animal, and ecosystem health—can provide early warning systems for emerging infectious diseases. By examining surveillance gaps and successes in tracking H5N1 across species, we demonstrate how comprehensive animal monitoring could help avert future global health crises.

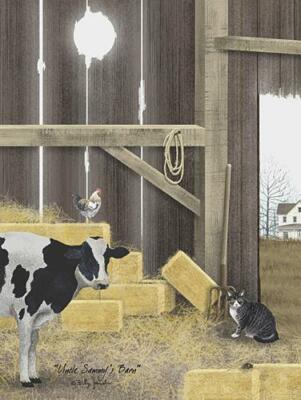

The detection of H5N1 avian influenza in US dairy cattle in early 2024 began not with sick cows, but with missing barn cats. This seemingly minor observation by a veterinarian in the southwestern United States unraveled a major outbreak affecting over 1,000 herds across 18 states by September 2025. This incident underscores a fundamental truth in pandemic prevention: animal health surveillance serves as our first line of defense against emerging infectious diseases that could threaten human populations. The interconnectedness of human, animal, and ecosystem health—known as the One Health approach—provides a framework for understanding how monitoring wildlife, livestock, and companion animals can offer crucial early warnings.

The One Health Framework and Pandemic Prevention

The One Health perspective recognizes that human health is inextricably linked to the health of animals and our shared environment. Approximately 75% of emerging infectious diseases in humans originate from animals, making animal surveillance not just an agricultural concern but a critical public health imperative. The H5N1 outbreak demonstrates this connection perfectly: a virus circulating in wild birds jumped to dairy cattle, then to barn cats, creating multiple pathways for potential human exposure. This multi-species transmission chain highlights why isolated surveillance systems focused solely on human health or single animal sectors are insufficient for comprehensive pandemic prevention.

Surveillance Successes: The US Dairy Outbreak Case

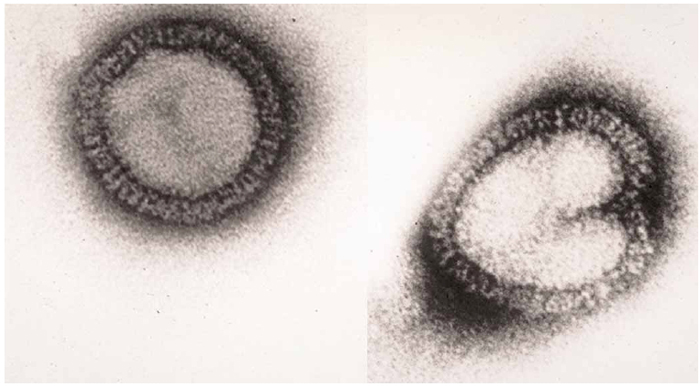

The detection of H5N1 in US dairy cattle offers both a cautionary tale and a model for effective surveillance. For weeks, veterinarians observed puzzling symptoms in cows—reduced appetite, decreased milk production, and abnormal milk consistency—while simultaneously noting unusual bird and cat deaths. Traditional disease testing failed to identify the cause until samples were sent to the National Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory in Iowa. The breakthrough came from testing both bovine milk samples and tissue from deceased barn cats, which simultaneously tested positive for H5N1. This multi-species diagnostic approach was crucial, as the virus had never been known to infect cattle before this outbreak.

Following detection, Colorado implemented an innovative surveillance strategy that became a national model: weekly testing of samples from bulk milk tanks. This approach built upon existing food safety protocols to detect infected herds before cows showed symptoms, allowing for earlier quarantine measures. The success of bulk-tank testing in Colorado—where dairy herds remained H5N1-free by late July 2025—demonstrates how integrating surveillance into routine agricultural practices can provide effective early warning systems.

Global Surveillance Gaps and Challenges

Despite these successes, significant gaps remain in global animal health surveillance. The current H5N1 outbreak, caused by clade 2.3.4.4b, has revealed the limitations of existing systems. The virus has infected over 500 species of wild birds across diverse taxonomic groups and at least 80 mammal species, demonstrating an unprecedented host range. Yet wildlife surveillance remains under-resourced in many regions, with some countries lacking funding for comprehensive monitoring programs. In the United States, proposed budget cuts threaten key surveillance components, including biological research at the US Geological Survey that supports wild-bird monitoring.

Companion animal surveillance represents another critical gap. During the US outbreak, about 100 domestic cats died from H5N1, primarily barn cats or feral animals. However, there is little organized surveillance of H5N1 in companion animals globally. Government agencies often lack authority to track emerging diseases in domestic pets, creating blind spots in our understanding of transmission pathways. Some states have incorporated H5N1 testing into rabies protocols for cats with neurological symptoms, but this captures only a fraction of potential cases.

Building a More Resilient Surveillance System

To strengthen pandemic prevention, animal health surveillance must become more comprehensive, integrated, and adequately funded. Key improvements include expanding monitoring beyond agricultural species to include wildlife and companion animals, developing more efficient surveillance methods such as environmental sampling of guano, and ensuring sustained funding for long-term monitoring programs. The Arctic and Antarctic regions, where migratory bird flyways converge, represent particularly important surveillance priorities for understanding viral evolution and dispersal.

Equally important is fostering collaboration between human public health agencies, veterinary services, wildlife experts, and environmental scientists. The siloed nature of current surveillance systems hampers our ability to detect and respond to cross-species disease threats. By breaking down these barriers and adopting a truly integrated One Health approach, we can create surveillance networks that provide earlier warnings of emerging threats.

Conclusion: Investing in Prevention

The 2024 H5N1 outbreak in US dairy cattle serves as a powerful reminder that animal health is human health. The barn cats that first signaled this outbreak were more than just farm animals—they were sentinels in a complex ecological web. By investing in comprehensive animal health surveillance, we invest in pandemic prevention. This requires sustained funding, interdisciplinary collaboration, and a commitment to monitoring the health of all species within our shared ecosystems. As pathogens continue to cross species barriers in our interconnected world, robust animal surveillance may well provide the critical early warning needed to avert the next pandemic.