Preventing the Next Pandemic: The Critical Battle Against H5N1 Bird Flu

The H5N1 avian influenza virus has evolved from a poultry disease to a multi-species threat, with recent jumps to dairy cattle raising serious pandemic concerns. This article examines the current outbreak in the United States, exploring how the virus spreads between wild birds, cattle, and poultry, and why controlling it has proven so difficult. We analyze the challenges in implementing effective biosecurity measures, the debate around vaccination strategies, and the critical need for a comprehensive national plan to protect both animal and human health before this virus acquires the mutations needed for efficient human-to-human transmission.

The specter of a new influenza pandemic looms larger than it has in years, not from a distant corner of the globe, but from within the heart of American agriculture. The H5N1 avian influenza virus, once primarily a threat to poultry, has breached a new frontier: dairy cattle. This unexpected jump has placed infectious disease specialists on high alert, transforming a manageable agricultural issue into a potential public health crisis. The story began for many consumers with empty supermarket shelves and exorbitant egg prices, but the underlying narrative is one of a virus adapting, spreading through new mammalian hosts, and inching closer to the genetic changes that could enable a devastating human pandemic. This article explores the complex challenge of stopping H5N1, examining the science of spillover, the economic and logistical hurdles to control, and the urgent steps needed to protect global health.

The Spillover: From Birds to Cattle

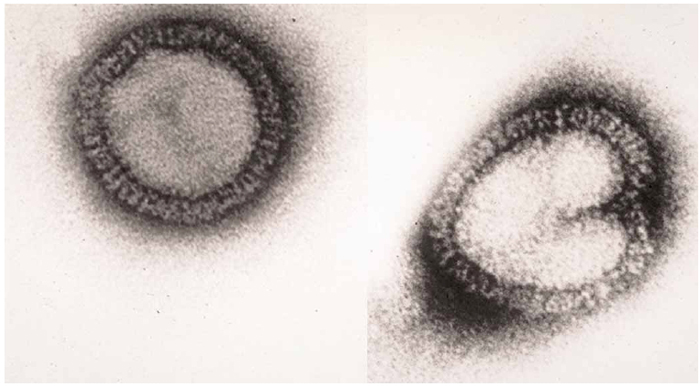

The current global crisis traces its origins to a fundamental change in the virus's behavior. The H5N1 clade now circulating has demonstrated an alarming ability to infect dozens of animal species beyond birds, including seals, cats, and mice. However, its move into dairy cattle represents the most significant escalation. Evidence suggests the initial spillover event occurred in December 2023, when the virus, carried by wild birds, found a susceptible host in cows. Researchers initially believed this was a unique event tied to a specific viral genotype called B3.13. This assumption was shattered when a different genotype, D1.1, independently jumped from wild birds to cattle on at least two other occasions.

This repeated cross-species transmission indicates a troubling new normal. The interface between dairy farms and wild bird habitats is a key vulnerability. Unlike poultry, which are often raised indoors, dairy cattle frequently share pastures, water sources, and feed with wild birds. As noted by epidemiologist Maurice Pitesky, farm locations near prime waterfowl habitat or wastewater lagoons create perfect conditions for viral exchange. The solution isn't to rebuild farms but to implement deterrents—using nets, lasers, or sound cannons to make farms less attractive to birds and thereby reduce the constant opportunity for spillover.

The Control Conundrum in Dairy Herds

Containing H5N1 in dairy cattle presents a fundamentally different challenge than in poultry. In birds, the virus is highly lethal, prompting strict culling policies and generally strong biosecurity. In cows, however, H5N1 causes a milder illness—reduced milk production and appetite—but rarely death. This milder presentation has led to a less aggressive control strategy focused on identifying and isolating sick animals, a approach some experts criticize as inadequate.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) recommends biosecurity measures like disinfecting vehicles, treating infected milk, and using personal protective equipment (PPE). Yet, without significant economic incentive or visible animal mortality, compliance among dairy producers is low. As veterinarian Keith Poulsen notes, the impetus for change may only come if cows start dying. Furthermore, the structure of dairy farming works against containment. Farms often operate on a continuous production cycle, constantly introducing new, immunologically naive animals. Herds can be geographically dispersed, with calves, breeding stock, and lactating cows on separate farms, making a complete production halt impossible. The result, as described by California's state veterinarian, is herds remaining under quarantine and potentially shedding virus for over 300 days.

The Domino Effect on Poultry and Humans

The virus's persistence in cattle creates a dire threat for neighboring poultry operations. A single infected cow sheds enough virus to devastate an entire poultry farm. The 2024 outbreak saw 28 million of the 39 million egg-laying hens lost in the U.S. linked to spillover from nearby dairies. A stark example occurred at Hickman's Family Farms in Arizona, where the virus jumped from a dairy, necessitating the culling of 6 million birds. For egg producers, this represents an existential threat fueled by a problem in a different agricultural sector.

The risk to human health, while currently limited, is the ultimate concern. The more the virus circulates in mammals like cattle, the greater the chance it will acquire mutations for efficient human-to-human transmission. While 70 human cases have been confirmed in the U.S., serology studies suggest the true number is higher, with many infections being asymptomatic or mild. Protecting farm workers is paramount, but CDC recommendations for full PPE see dismal compliance, often below 5%. The equipment is hot, cumbersome, and impractical for daily farm work. Experts like Michelle Kromm argue for smarter, more tolerable biosecurity—perhaps cotton coveralls instead of plastic, or exit showers—to improve worker safety without sacrificing feasibility.

Vaccination: A Controversial Tool in the Toolbox

Many specialists see vaccination of dairy cattle as a critical missing piece of the puzzle. As stated in congressional testimony, the tool is needed "yesterday." At least two companies are developing bovine vaccines, with the goal of reducing viral shedding, thereby protecting workers and neighboring farms. The precedent exists in poultry; countries like China and Mexico vaccinate their flocks against H5N1.

However, vaccination in the U.S. faces significant hurdles. The poultry industry, particularly meat producers, has historically opposed vaccination over fears it would trigger export bans from trade partners worried about masking infections. For egg producers like Hickman's, who have suffered catastrophic losses, the calculus is different. They advocate for access to vaccines to build flock resilience alongside biosecurity. The debate highlights a tension between different agricultural sectors and international trade policies, all while the virus continues to spread.

Toward a Comprehensive National Strategy

The current fragmented response—milk testing here, movement restrictions there—is insufficient. Experts like virologist Thomas Friedrich warn that the nation is in a worse position to respond to a pandemic now than in 2020, with public health measures heavily politicized. A clear, unified plan is urgently needed. This plan must address all susceptible species, fund research to understand transmission pathways (whether by wind, equipment, or insects), and support the development and deployment of vaccines.

Equally important is building trust with the agricultural workforce, ensuring they can report symptoms without fear, and providing them with effective, practical protection. The goal is not just to manage an agricultural outbreak but to prevent a viral lineage from gaining the final adaptations required to launch the next global influenza pandemic. The time for a comprehensive, science-led national strategy is now, before the virus makes the next, irreversible move.