The Global Race to Develop and Stockpile H5N1 Bird Flu Vaccines

As H5N1 avian influenza continues to spread among birds and mammals worldwide, health authorities and vaccine manufacturers are engaged in a complex balancing act: preparing for a potential pandemic without wasting resources on a threat that may never fully materialize. This article explores the current state of H5N1 vaccine development, examining the technologies being used, the challenges of production timelines, and the global stockpiling strategies being implemented by countries like Finland and the United States. We analyze why this particular virus strain is causing concern, the limitations of current vaccine platforms, and the emerging role of mRNA technology in pandemic preparedness.

The specter of a deadly avian influenza pandemic has loomed over global health authorities for decades, but recent widespread outbreaks of the H5N1 strain among mammals have intensified concerns and accelerated vaccine development efforts. Unlike seasonal flu, H5N1 poses a unique threat due to its high mortality rate in historical human cases and its unprecedented spread across bird and mammal populations. The current global response involves a delicate dance between proactive preparedness and pragmatic resource allocation, as scientists and governments attempt to hatch a viable defense against a virus that has not yet learned to spread efficiently between humans.

Understanding the H5N1 Threat

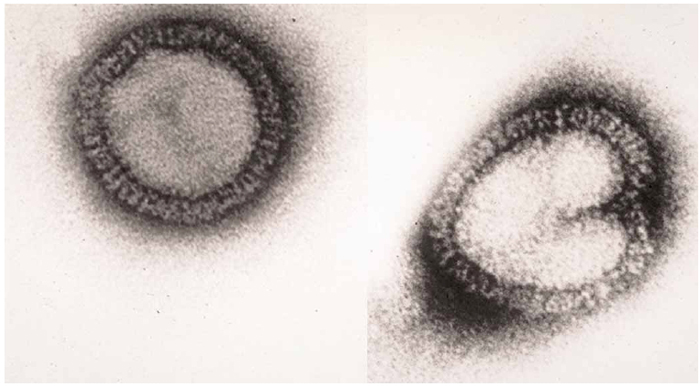

Influenza A viruses, which include H5N1, are categorized by two surface proteins: haemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). The H5N1 subtype has a concerning history. Since 2003, nearly 1,000 confirmed human infections have occurred, primarily through direct contact with sick animals, resulting in a fatality rate of roughly 50%. The current dominant form, known as the 2.3.4.4b clade, is particularly alarming to microbiologists because it has infected a wider variety of bird and mammal species than any predecessor. Despite this, human cases remain relatively rare and often mild, with only 70 reported in the United States as of mid-2025, mostly among dairy and poultry workers. The critical fear is that the virus could mutate to bind efficiently to human upper airway receptors, enabling efficient airborne transmission—a single genetic change that researchers have shown is possible in laboratory settings.

The Vaccine Arsenal: Current Platforms and Players

Several pharmaceutical companies are at the forefront of developing H5N1-specific vaccines. CSL Seqirus, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Pasteur, and AstraZeneca have all created shots targeted for human use. A critical challenge is that immunity from seasonal flu vaccines offers little cross-protection against H5N1 because the shared genetic sequences are in the protein "stalk" rather than the "head," which is the target of traditional shots. Consequently, dedicated H5 vaccines are essential. Currently, all approved H5N1 vaccines are manufactured using the same decades-old processes as seasonal flu shots: growing the virus in either fertilized chicken eggs or mammalian cell cultures. The Seqirus vaccine, for instance, was used in Finland's pioneering 2024 vaccination program for high-risk groups following an outbreak on fur farms.

The Production Bottleneck

A major drawback of egg-based and cell-culture production is time. Creating a new batch from scratch takes up to six months—a critical delay if a pandemic begins to rage. The process involves incubating eggs for weeks, inoculating them with the virus, then harvesting, inactivating, and purifying the viral antigens. This system is vulnerable to disruptions, such as poultry disease outbreaks causing egg shortages. Furthermore, viruses can mutate or "drift" when grown in eggs, potentially reducing the vaccine's effectiveness against the circulating strain. While cell-culture methods avoid some avian-adaptation mutations, they do not significantly speed up the overall production timeline.

Global Stockpiling Strategies and Challenges

Nations are adopting varied approaches to H5N1 vaccine preparedness. Finland became the first country to proactively vaccinate high-risk individuals using the Seqirus shot. The European Union has collectively stockpiled 665,000 doses for similar targeted use and has pre-purchased 112 million doses of pandemic-preparedness vaccines that can be rapidly approved and deployed if a pandemic is declared. The United States reportedly aimed to stockpile 10 million doses by early 2025, which would cover only about 1.5% of its population with a two-dose regimen. However, the urgency has waned publicly as human cases have declined, leading to criticism from public health experts who warn against complacency.

The Promise and Politics of mRNA Technology

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated the revolutionary speed of messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccine platforms, which can be designed and produced in approximately three months without needing to grow a live virus. This technology is now being applied to influenza. Pfizer has reported positive Phase I trial results for an mRNA vaccine against the 2.3.4.4b clade of H5N1, and other entities, including GlaxoSmithKline and the U.S. National Institutes of Health, are pursuing similar candidates. Research has shown these vaccines can protect animal models from lethal H5N1 challenge. However, the technology faces political headwinds and misinformation, impacting funding and public acceptance, which could hinder its deployment in a crisis.

Conclusion: A Precautionary Balancing Act

The quest to hatch an effective H5N1 vaccine strategy is a global gamble. Health authorities must invest in surveillance, research, and limited stockpiling without knowing if the feared pandemic will ever occur. The ideal portfolio includes both traditional, stockpiled vaccines for immediate deployment to frontline workers and flexible mRNA platforms that can be rapidly scaled to match an emerging viral threat. As the virus continues to circulate and evolve in animal reservoirs, maintaining this preparedness—and public trust in vaccines—remains one of modern public health's most critical and complex challenges. The lesson from past pandemics is clear: when a deadly virus learns to spread among humans, time is the most valuable resource, and preparation is the only defense.