Unveiling California's Hidden Seismic Danger: How Tiny Earthquakes Reveal a Complex Fault System

Scientists are using swarms of imperceptibly small earthquakes to map a surprisingly intricate and dangerous fault system beneath Northern California. This research, focused on the Mendocino Triple Junction where the San Andreas fault meets the Cascadia subduction zone, has uncovered five moving tectonic pieces instead of the expected three. The findings, published in Science, challenge long-held assumptions about the region's structure and provide crucial new data for assessing earthquake risks in one of North America's most seismically hazardous areas.

Beneath the rugged coastline of Northern California lies one of the most seismically complex and dangerous regions in North America. For decades, scientists have recognized the threat posed by the meeting of the San Andreas fault and the Cascadia subduction zone, but the true structure of this underground crossroads remained largely hidden. Now, researchers are gaining unprecedented insight by tracking earthquakes so small they're thousands of times weaker than anything humans can feel. This groundbreaking approach is revealing a far more complicated tectonic arrangement than previously imagined, with significant implications for earthquake hazard assessment in California and the Pacific Northwest.

The Mendocino Triple Junction: A Seismic Crossroads

The focus of this research is the Mendocino Triple Junction, located offshore from Humboldt County. This is where three major tectonic plates—the Pacific, North American, and Gorda (or Juan de Fuca) plates—converge in a geological puzzle that has long challenged seismologists. South of this junction, the Pacific plate moves northwest alongside the North American plate along the famous San Andreas fault. To the north, the Gorda plate moves northeast and sinks beneath the North American plate in a process called subduction, creating the Cascadia subduction zone.

As research published in Science reveals, what appears relatively straightforward on a map becomes astonishingly complex beneath the surface. "If we don't understand the underlying tectonic processes, it's hard to predict the seismic hazard," explains coauthor Amanda Thomas, professor of earth and planetary sciences at UC Davis. This understanding gap became particularly evident after a magnitude 7.2 earthquake in 1992 struck at a much shallower depth than scientists had predicted, suggesting their models of the region's structure were incomplete.

Listening to Earth's Whispers: The Power of Tiny Tremors

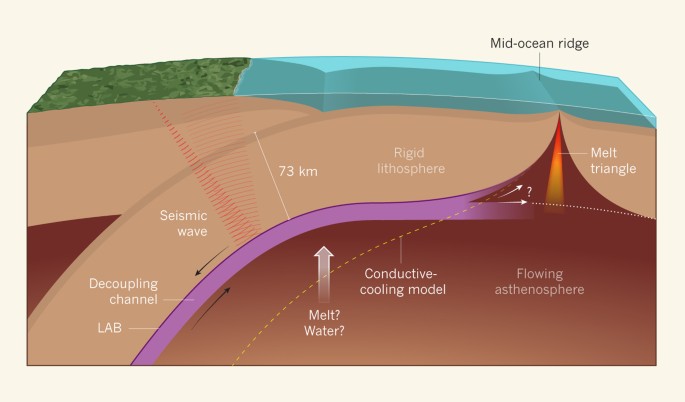

To uncover the hidden structure, researchers from the U.S. Geological Survey, University of California, Davis, and University of Colorado Boulder employed an innovative approach. They used a dense network of seismometers across the Pacific Northwest to detect extremely small "low-frequency" earthquakes that occur where tectonic plates slowly slide against or over one another. These faint tremors are essentially Earth's whispers—far too weak to be felt at the surface but rich with information about subsurface structures.

First author David Shelly of the USGS Geologic Hazards Center compares the challenge to studying an iceberg: "You can see a bit at the surface, but you have to figure out what is the configuration underneath." The team tested their underground model by examining how these small earthquakes respond to tidal forces. Just as the gravitational pull of the Sun and Moon affects ocean tides, it also places subtle stress on tectonic plates. When those forces align with the natural direction of plate movement, the number of small earthquakes increases, providing valuable clues about subsurface fault orientations and movements.

Five Moving Pieces: A Revised Tectonic Model

The most significant finding from this research is that the region involves five moving tectonic pieces rather than just the three major plates visible at the surface. The team discovered two previously hidden fragments being dragged beneath North America. At the southern end of the Cascadia subduction zone, a portion of the North American plate has broken away and is being pulled downward along with the sinking Gorda plate.

South of the triple junction, researchers identified what they call the Pioneer fragment—a mass of rock that the Pacific plate is pulling beneath the North American plate as it moves northward. The fault separating the Pioneer fragment from the North American plate lies nearly flat and cannot be seen at the surface. This fragment was once part of the Farallon plate, an ancient tectonic plate that once extended along the California coastline and has since mostly disappeared beneath North America.

Implications for Earthquake Hazard Assessment

This revised tectonic model helps explain why the 1992 earthquake occurred at such an unexpectedly shallow depth. According to the research, the surface being pushed beneath North America is not as deep as scientists previously believed. "It had been assumed that faults follow the leading edge of the subducting slab, but this example deviates from that," notes researcher Kathryn Materna. "The plate boundary seems not to be where we thought it was."

The discovery of these hidden fragments and the more complex fault geometry has significant implications for understanding earthquake risks in the region. A more accurate model of subsurface structures allows for better predictions of how stress accumulates and releases along faults, which is crucial for assessing the potential size and location of future earthquakes. This research represents a major step forward in seismic hazard mapping for Northern California and the Pacific Northwest.

As scientists continue to refine their understanding of this complex region, the approach of monitoring tiny earthquakes promises to reveal more secrets about Earth's subsurface structures. This work, supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation, demonstrates how listening to Earth's faintest whispers can help us better prepare for its loudest roars—potentially saving lives and property in one of North America's most seismically active regions.