Titan's Strong Tidal Dissipation Challenges the Existence of a Subsurface Ocean

A groundbreaking reanalysis of Cassini mission data reveals that Saturn's largest moon, Titan, exhibits unexpectedly strong tidal dissipation, a finding that challenges the long-held belief in a global subsurface ocean. The new measurements of Titan's complex tidal Love number indicate substantial energy dissipation within its interior, consistent with a model featuring a high-pressure ice layer near its melting point. This discovery not only redefines our understanding of Titan's internal structure but also has profound implications for the search for habitable environments on icy moons throughout the solar system.

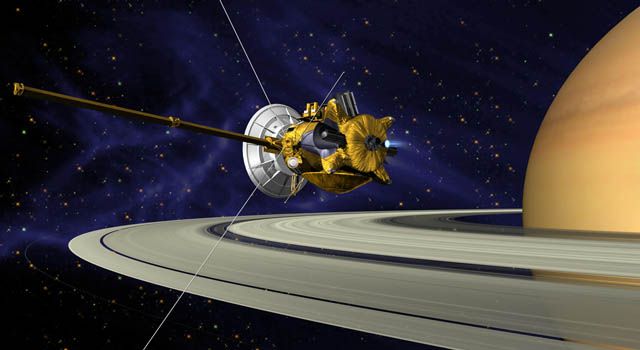

For decades, planetary scientists have theorized that Saturn's largest moon, Titan, harbors a global subsurface ocean beneath its icy crust—a potential habitat for extraterrestrial life. This hypothesis gained substantial support from data collected by NASA's Cassini mission, which orbited Saturn from 2004 to 2017. However, a landmark study published in Nature presents a compelling challenge to this prevailing view. A sophisticated reanalysis of Cassini's radio tracking data has yielded the first direct measurement of the imaginary component of Titan's tidal Love number, revealing unexpectedly strong tidal dissipation that is inconsistent with the presence of a global liquid water layer. This finding points toward a radically different interior model for Titan, one dominated by a slushy, high-pressure ice shell.

Decoding Titan's Tidal Response

The key to understanding a moon's interior lies in measuring its response to gravitational tides from its parent planet. This response is quantified by the complex tidal Love number, k₂. The real part, Re(k₂), measures the amplitude of the tidal bulge, while the imaginary part, Im(k₂), measures the phase lag caused by energy dissipation within the moon's interior. A large Re(k₂) has traditionally been interpreted as strong evidence for a global fluid layer, as liquids enhance tidal deformation. However, as noted in pre-Cassini studies, substantial viscoelastic deformation in a solid interior could produce a similar signal. The detection of Im(k₂) was therefore identified as the critical test to break this model degeneracy.

Previous analyses of Cassini data successfully measured Titan's Re(k₂), finding a value of approximately 0.616, which was widely interpreted as confirmation of a subsurface ocean. Yet, these studies could not confidently detect Im(k₂). The new research, employing improved data processing techniques including phase-averaging algorithms developed for the Juno and InSight missions, has achieved this crucial measurement. The results are striking: Im(k₂) = 0.135 ± 0.035. This value is three to four times larger than the maximum expected for a body with a global ocean and corresponds to a tidal quality factor (Q) of about 5, indicating exceptionally strong internal dissipation. For context, Earth's Q is approximately 300 and Mars's is about 90.

A New Model for Titan's Interior

The measured tidal dissipation presents a significant problem for the ocean model. A global liquid layer acts to reduce tidal dissipation in the layers beneath it. The new data shows dissipation is too high to be compatible with this configuration. Through Bayesian interior modeling, the research team demonstrates that the observations are best explained by a model without a global ocean.

Instead, the model that fits all geophysical constraints—mass, moment of inertia, Re(k₂), and Im(k₂)—features a multi-layered hydrosphere. The structure consists of a roughly 170 km thick outer shell of low-pressure ice (Ice Ih), underlain by a approximately 378 km thick layer of high-pressure ice polymorphs (Ice III, V, and VI) sitting atop a large, low-density rocky core. The intense tidal dissipation, generating about 3–4 terawatts of heat, is concentrated in this high-pressure ice layer, which must have an average viscosity as low as 10¹² Pascal-seconds, indicating it is very close to its melting point throughout its depth.

Thermal State and Implications for Habitability

The absence of an ocean raises immediate questions about Titan's thermal evolution. The study shows that efficient convection in the outer ice shell can remove the substantial tidal heat without causing widespread melting, preventing an ocean from forming. This finding suggests that ocean worlds may be less common than previously assumed. However, the proposed "slushy" state of the high-pressure ice layer may create a new paradigm for potential habitability.

Even a small melt fraction (e.g., 1%) within this extensive hydrosphere would create a liquid volume comparable to Earth's Atlantic Ocean. These melt pockets, potentially enriched with organic and saline solutions transported from the rocky core or the surface, could form unique cryoecological niches. Such environments could be analogous to Earth's polar sea ice ecosystems, which support diverse life despite extreme conditions.

Broader Implications for Planetary Science

This discovery has ramifications beyond Titan. It underscores the necessity of measuring both components of the tidal Love number to accurately characterize the interiors of large icy moons. The upcoming JUICE mission to Ganymede is expected to make similarly precise measurements, which will provide a fascinating comparative data point. The research also impacts our understanding of orbital dynamics within the Saturnian system. Titan's strong internal dissipation causes its orbital eccentricity to damp on a surprisingly short timescale of about 30 million years, implying its current orbit is not primordial and that the Saturn system has experienced recent dynamical evolution.

The forthcoming NASA Dragonfly mission, a rotorcraft lander scheduled to explore Titan's surface in the 2030s, will provide a critical test of this new model. Dragonfly's geophysical instruments, including a seismometer, could detect the layering of ice polymorphs and help constrain the distribution of fluids within Titan's hydrosphere.

In conclusion, the revelation of Titan's strong tidal dissipation represents a major shift in planetary science. It moves Titan from the category of a classic "ocean world" to a more complex body with a vast, partially molten, high-pressure ice mantle. This not only redefines Titan's astrobiological potential but also provides a crucial reminder that our understanding of planetary interiors must continually evolve with new, precise measurements. The study, detailed in Nature, exemplifies how reanalyzing legacy data with advanced techniques can yield transformative discoveries.