Rewiring Vision: How Surviving Neurons Restore Sight After Injury

A groundbreaking neuroscience study challenges the long-held belief that damaged neurons cannot regenerate. Research from Johns Hopkins University reveals that after traumatic injury to the visual system, surviving eye cells can grow new branches to re-establish connections with the brain, effectively restoring visual function. This process, known as compensatory sprouting, offers a new understanding of neural recovery. Intriguingly, the study found significant sex differences, with female mice showing slower or incomplete repair compared to males, highlighting important biological variations in recovery mechanisms that could inform future treatments for brain injuries and concussions.

For decades, a fundamental principle of neuroscience has been that neurons, once damaged or destroyed, do not regenerate. This dogma has profoundly influenced our understanding and treatment of brain injuries. Yet, clinical observation tells a more hopeful story: people often regain lost abilities after trauma. A pivotal new study published in The Journal of Neuroscience resolves this paradox, revealing a remarkable mechanism by which the visual system heals itself not by growing new cells, but by ingeniously rewiring the ones that survive.

The Mechanism of Compensatory Sprouting

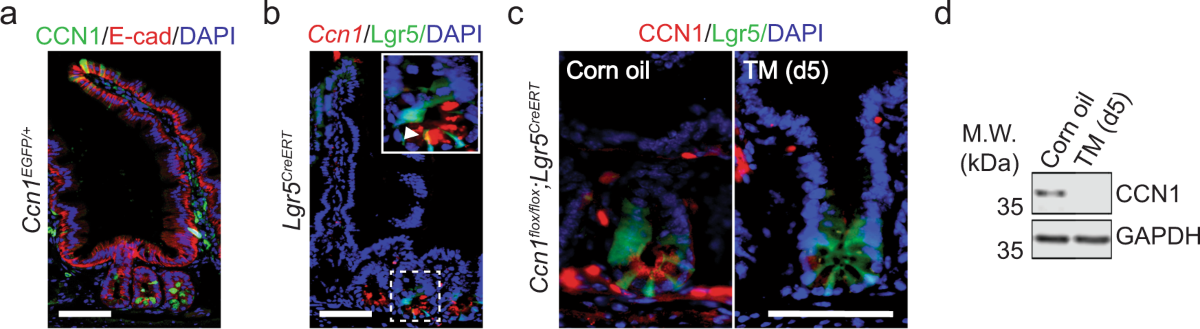

Led by researchers at Johns Hopkins University, the study investigated recovery in the mouse visual system following traumatic brain injury. The visual system comprises specialized cells in the retina that transmit visual information to specific neurons in the brain. When this pathway is damaged, communication breaks down, leading to vision impairment. Contrary to expectations of cell regrowth, the team discovered a process called compensatory sprouting.

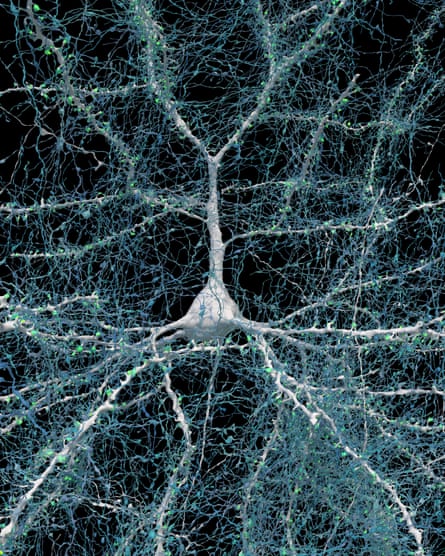

The surviving retinal cells did not simply remain idle. Instead, they actively grew additional neuronal branches, or axons. This sprouting allowed a single surviving cell to form connections with more brain neurons than it did prior to the injury. Over time, this adaptive rewiring restored the overall number of eye-to-brain connections to near-normal, pre-injury levels. Crucially, electrophysiological measurements confirmed that these newly formed pathways were functional, capable of transmitting electrical signals and restoring visual processing.

Uncovering Significant Sex Differences in Recovery

One of the most striking findings of the research was a clear divergence in recovery rates between male and female subjects. While male mice exhibited robust restoration of visual connections through sprouting, female mice showed a slower, and often incomplete, repair process. Their neural pathways did not consistently rebound to pre-injury levels.

This discovery aligns with broader clinical patterns where women frequently report more persistent symptoms following concussions and traumatic brain injuries than men. As lead author Athanasios Alexandris noted, understanding why this sprouting mechanism is less efficient in females is a critical next step. Identifying the biological factors—which could involve hormones, immune responses, or genetic regulators—that delay repair could unlock novel therapeutic strategies to promote recovery for all patients.

Implications for Future Treatment and Research

This research fundamentally shifts the paradigm for understanding neural recovery. It moves the focus from the impossible task of replacing dead neurons to the achievable goal of enhancing the innate plasticity of surviving cells. The findings, detailed in the original study, suggest that future therapies for brain injury, stroke, or neurodegenerative diseases might aim to pharmacologically stimulate or support this natural sprouting process.

Furthermore, the identified sex difference underscores the necessity of including both male and female subjects in preclinical research. Developing effective, personalized treatments requires a nuanced understanding of how biological sex influences disease mechanisms and healing. The Johns Hopkins team plans to continue this work, investigating the molecular signals that initiate sprouting and the barriers that impede it in females.

In conclusion, the brain's capacity for healing is more dynamic than previously believed. Through the adaptive rewiring of surviving neurons, the visual system can overcome significant injury. This discovery not only illuminates a path to restored vision but also offers a beacon of hope for repairing other neural circuits damaged by trauma or disease, provided we tailor our approaches to the biological realities of each patient.