The Global Impact of a Cancer-Causing Gene in Sperm Donation

An international investigation has revealed that sperm from a single donor, who unknowingly carried a mutation in the TP53 cancer-suppressing gene, was used to conceive nearly 200 children across 14 countries. The mutation causes Li-Fraumeni syndrome, which carries a 90% lifetime cancer risk. This case highlights critical gaps in genetic screening protocols, international regulatory disparities, and the profound ethical challenges in the global fertility industry, where a donor's genetic material was distributed by 67 different clinics.

The global fertility industry, built on hope and advanced science, is confronting a profound ethical and medical crisis. An international investigation has uncovered that sperm from a single donor, who unknowingly carried a hereditary cancer-causing gene, was used to conceive children across continents. This case exposes critical vulnerabilities in genetic screening, international regulatory frameworks, and the far-reaching consequences when a biological sample becomes a global commodity.

The Discovery and the Genetic Defect

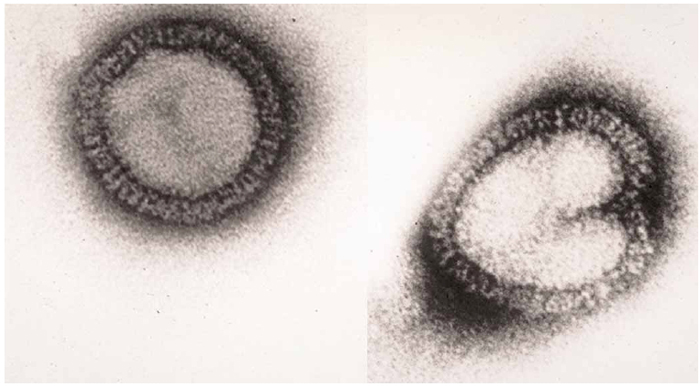

The donor was a healthy 17-year-old student in 2005 when he passed all standard screening checks required for donation. However, a mutation had occurred in his cells before birth, damaging the TP53 gene. This gene is crucial as a tumor suppressor, playing a vital role in preventing cancerous cells from multiplying. While most of the donor's body did not contain the damaged gene, the investigation found that up to 20% of his sperm cells carried the mutation.

Any child conceived from an affected sperm cell inherits the mutation in every cell of their body. This results in Li-Fraumeni syndrome, a genetic disorder that dramatically increases the lifetime risk of developing various cancers, including brain tumors, leukemia, and breast cancer. According to the investigation, there is a 90% chance that individuals with this syndrome will develop cancer, necessitating a lifetime of intensive medical surveillance.

Global Scale and Human Toll

The scope of this case is staggering. The donor's sperm was used for approximately 17 years. It was distributed by Denmark's European Sperm Bank and utilized by 67 different fertility clinics located in 14 different countries. At least 197 children have been born from this donor's sperm. The human impact is devastating. Among the 67 children known to doctors at the time of a recent presentation, 23 carried the mutation, and 10 had already received a cancer diagnosis. Tragically, some children have developed multiple cancers, and some have died at a very young age.

Parents of the affected children are now being contacted by clinics and urged to have their children screened. The psychological burden is immense, as described by Prof. Clare Turnbull, a cancer geneticist at the Institute of Cancer Research in London, who called it "a dreadful diagnosis" and "a lifelong burden of living with that risk."

Regulatory Failures and International Disparities

This case underscores a patchwork of international regulations with significant gaps. There is no single, global law limiting the number of offspring from a single sperm donor. Individual countries set their own limits, which were blatantly breached in this instance. For example, in Belgium, regulations stipulate that a donor can be used by a maximum of six families. The investigation found that 38 women in Belgium had given birth to 53 children using this donor's sperm.

In North America, the regulatory landscape is similarly fragmented. In Canada, there is no federal cap on the number of families that can use one donor, though provinces and individual clinics may set rules. Quebec, for instance, limits donors to 10 families. In the United States, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine provides non-binding guidelines suggesting a limit of 20-25 offspring per donor to mitigate risks of genetic concentration and accidental consanguinity, but these are not legally enforced.

Screening Protocols and Inherent Limitations

The case reveals a critical limitation in current donor screening practices. Health Canada's protocol, as outlined to Global News, involves a physical exam, a structured questionnaire, and testing for infectious diseases like HIV and syphilis. However, as both the European Sperm Bank and the BBC noted, routine genetic screening does not proactively detect specific cancer-causing gene mutations like the one in the TP53 gene. Donors are screened for known family histories of genetic disease, but de novo mutations—those that occur spontaneously—can slip through.

This gap highlights a fundamental challenge: balancing the cost and feasibility of comprehensive whole-genome sequencing for all donors against the rare but catastrophic risk of transmitting serious genetic conditions. The fertility industry operates on a model of presumed donor health based on available screenings, but this case proves that model can fail with tragic consequences.

Ethical and Industry Reckoning

The European Sperm Bank, which sold the sperm, has expressed its "deepest sympathy" to affected families and acknowledged that the sperm was "used to conceive too many babies in some countries." The donor sperm was removed from circulation only after the mutation was discovered. This incident forces a difficult ethical reckoning regarding anonymity, donor responsibility, and the commercial scale of gamete donation.

The drive for donor anonymity, often protected by law to encourage donation, clashes with the modern need for comprehensive genetic histories. Furthermore, the commercial distribution of a single donor's sperm across dozens of clinics in multiple countries turns a personal biological donation into a mass-produced product, amplifying the impact of any undetected defect.

Conclusion and Path Forward

The story of these nearly 200 children is a sobering lesson in the complexities of modern reproductive medicine. It demonstrates that biology does not respect national borders or clinic consent forms. Moving forward, this tragedy must catalyze action. There is a pressing need for international dialogue on harmonizing stricter donor offspring limits. The fertility industry must also re-evaluate the ethical imperative and practical feasibility of expanding genetic screening panels. Most importantly, it reaffirms that behind every vial of sperm or embryo is a potential human life, demanding the highest possible standard of care, vigilance, and ethical responsibility from clinics and regulators worldwide. Supporting affected families with lifelong medical and psychological care must be an immediate priority as the long-term consequences of this systemic failure continue to unfold.