US Vaccine Advisors to Vote on Reversing Universal Hepatitis B Birth Dose Recommendation

A pivotal vote by the US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) on Friday could rescind a decades-old policy recommending all newborns receive a hepatitis B vaccine at birth. This universal 'birth dose' has been credited with a 99% reduction in hepatitis B infections among Americans under 19 since 1991. The re-evaluation, prompted by concerns over public dissatisfaction with vaccination policy and alignment with other developed nations, has sparked debate among committee members. This article examines the rationale behind the policy, the arguments for and against change, and the potential public health implications of the committee's decision.

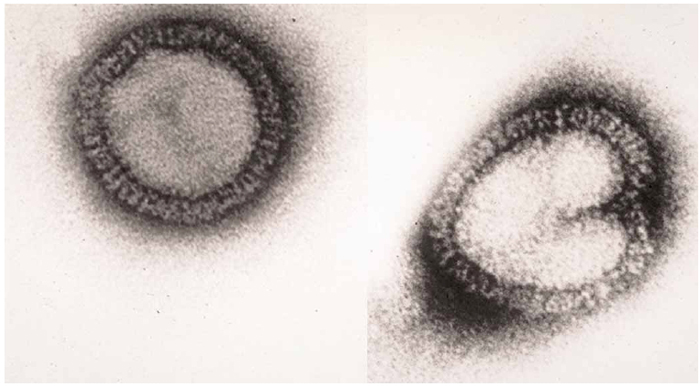

A critical vote scheduled for Friday by the US Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) could mark a significant shift in American pediatric vaccination policy. The committee will decide whether to rescind the long-standing recommendation that all healthy newborns receive a hepatitis B vaccine shortly after birth. This universal 'birth dose' policy, established in 1991, has been a cornerstone of US public health strategy, credited with dramatically reducing mother-to-child transmission of a virus that can cause chronic liver disease, cirrhosis, and cancer. The impending vote follows preliminary discussions where committee members raised questions about the necessity and safety of the practice, highlighting a tension between maintaining a successful public health intervention and responding to evolving societal concerns and international norms.

The outcome of this vote carries substantial weight for public health, clinical practice, and parental choice. As the committee prepares to deliberate, stakeholders are examining the evidence, the history of the policy's success, and the contemporary arguments driving its potential reversal.

The Current Policy and Its Proven Success

Since 1991, US public health guidelines have called for the universal hepatitis B vaccination of all newborn babies. This policy was implemented to combat a virus known for its potential to cause lifelong infection and severe liver complications. The results have been undeniably positive: according to data cited in Nature, the strategy helped drive down hepatitis B infections in Americans younger than 19 by a staggering 99%. The vaccine is highly effective at preventing infection when administered shortly after birth, particularly in blocking transmission from an infected mother to her child—a route responsible for a high rate of chronic infection.

The rationale for the birth dose extends beyond immediate protection. It serves as a safety net in a healthcare system with documented gaps. Not all pregnant individuals are tested for hepatitis B, and even when they are, screening is not perfect. A study analyzing over 500,000 US pregnancies from 2015 to 2019 found that nearly 15% of pregnant people were not tested at all. Furthermore, test sensitivity estimates range from 95% to 100%, meaning some infections can be missed. The universal birth dose ensures that infants born to mothers with undetected infections are protected from the moment they are most vulnerable.

Arguments Driving the Re-evaluation

The ACIP's decision to revisit this recommendation stems from several converging factors. A primary concern, as expressed by some committee members, is public dissatisfaction with vaccination policy. ACIP member Vicky Pebsworth, a nurse and health-policy analyst, referenced surveys indicating that 16% of parents report skipping or delaying childhood vaccines due to concerns about side effects and safety. "This level of dissatisfaction is of societal significance and poses challenges for vaccination policy making," Pebsworth noted during Thursday's discussions.

Another argument centers on international alignment. The US policy of universal birth-dose vaccination is described as "misaligned relative to existing recommendations in most other developed countries," where such a blanket approach is not standard practice. Some committee members have also raised questions about long-term safety, with ACIP member Evelyn Griffin, an obstetrician, suggesting that "sometimes autoimmune conditions take decades to develop." However, this concern was countered by Rochelle Walensky, former CDC director, who emphasized the robustness of US vaccine-safety monitoring, stating that over 35 years and millions of doses, "we have not detected those events."

Potential Implications of a Policy Change

If the ACIP votes to rescind the universal recommendation, the most likely alternative would be a targeted approach, vaccinating only infants born to mothers who test positive for hepatitis B. Proponents argue this aligns with the virus's primary transmission routes in low-prevalence countries like the US, where most infections are acquired during adulthood. However, public health experts warn of the risks inherent in relying solely on a screening-based strategy.

As infectious-disease epidemiologist Angela Ulrich explains, "there will be a number of infants who sneak through the cracks, who are missed by gaps in prenatal detection." These gaps include false-negative test results and lack of testing altogether. A recent study published on December 3, 2025, estimated that more than 600 mothers in the US still transmit the hepatitis B virus to their babies annually. Removing the universal safety net could lead to an increase in these preventable transmissions, potentially reversing decades of progress. The committee's challenge is to weigh the desire to address vaccine hesitancy and align with other nations against the proven efficacy of a policy that protects the most vulnerable infants from a serious disease.

Conclusion

The upcoming ACIP vote represents a critical juncture in US vaccination policy. The decades-old recommendation for a universal hepatitis B birth dose is a public health success story, having nearly eliminated the disease in American children. Yet, it now faces scrutiny driven by societal concerns, international comparisons, and philosophical debates about medical intervention. The committee's decision must be grounded in what Rochelle Walensky called "gold-standard, evidence-based science and common sense." Whether they choose to maintain a proven, protective blanket policy or shift to a more targeted approach, the implications will resonate through pediatric clinics and public health departments for years to come, ultimately affecting the health of the nation's newborns.