How a 70-Year-Old Pregnancy Drug Unlocks a New Weapon Against Brain Cancer

A decades-old mystery surrounding the pregnancy drug hydralazine has been solved by University of Pennsylvania researchers. They discovered the drug works by blocking a fast-acting cellular 'oxygen alarm' enzyme called ADO, which explains its blood pressure-lowering effect in preeclampsia. Intriguingly, this same oxygen-sensing pathway is exploited by aggressive brain tumors like glioblastoma to survive. The research reveals that hydralazine can disrupt this survival mechanism, forcing cancer cells into a dormant state. This unexpected link between maternal health and oncology opens new avenues for designing safer, more effective treatments for both conditions.

For over seven decades, the drug hydralazine has been a cornerstone in managing life-threatening high blood pressure during pregnancy, particularly in cases of preeclampsia. Yet, despite its widespread clinical use, a fundamental question remained unanswered: how exactly did it work at a molecular level? A groundbreaking study from the University of Pennsylvania has finally solved this mystery, revealing a mechanism of action that not only explains its efficacy in maternal health but also uncovers a surprising and potent new application in the fight against brain cancer. This discovery exemplifies how revisiting well-established treatments can reveal hidden biological connections and unlock novel therapeutic strategies.

The Long-Standing Mystery of Hydralazine

Hydralazine is one of the earliest vasodilators ever developed, originating from a "pre-target" era of drug discovery where clinical observations preceded a full biological understanding. As physician-scientist Kyosuke Shishikura from the University of Pennsylvania notes, it remains a first-line treatment for preeclampsia—a hypertensive disorder responsible for a significant percentage of maternal deaths worldwide. The lack of knowledge about its precise molecular target, however, limited the potential to improve its efficacy, safety, and therapeutic scope. The recent research, published in Science Advances, has now definitively identified this target.

Blocking the Cellular Oxygen Alarm

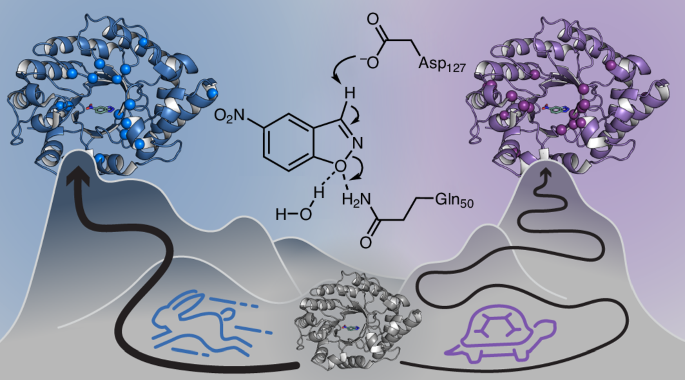

The research team discovered that hydralazine works by inhibiting an enzyme called 2-aminoethanethiol dioxygenase (ADO). This enzyme acts as a rapid-response "oxygen alarm" within cells. "ADO is like an alarm bell that rings the moment oxygen starts to fall," explains Megan Matthews, the study's senior investigator. Unlike most biological systems that require time to transcribe genes and build new proteins, ADO can flip a biochemical switch in seconds, initiating a cascade that constricts blood vessels.

By binding to and blocking ADO, hydralazine effectively mutes this alarm. This inhibition leads to the stabilization of specific signaling proteins known as regulators of G-protein signaling (RGS). As these RGS proteins accumulate, they signal blood vessels to stop constricting. This process reduces intracellular calcium levels—what Shishikura calls the "master regulator of vascular tension"—causing the smooth muscle in vessel walls to relax. The result is vasodilation and a subsequent drop in blood pressure, explaining hydralazine's long-observed therapeutic effect.

An Unexpected Link to Brain Cancer

The story took a remarkable turn when the researchers explored the role of ADO beyond cardiovascular function. Cancer biologists had previously suspected that ADO was crucial for aggressive brain tumors like glioblastoma, which often thrive in low-oxygen (hypoxic) environments within the brain. Elevated ADO levels were linked to more aggressive disease, suggesting that inhibiting it could be a powerful anti-cancer strategy, but a suitable inhibitor was lacking.

Collaborating with structural biochemists and neuroscientists, the Penn team tested hydralazine as a potential ADO inhibitor in brain cancer models. They found that the very same oxygen-sensing pathway that regulates blood vessel contraction also enables tumor cell survival under duress. When hydralazine blocked ADO in glioblastoma cells, it disrupted this critical survival loop. Instead of killing the cells outright—a approach that can trigger inflammation and resistance—the drug pushed them into a state of cellular senescence, a dormant, non-dividing condition that effectively halts tumor growth.

Implications and Future Directions

This discovery bridges two seemingly disparate fields: maternal-fetal medicine and neuro-oncology. It provides a clear biological rationale for hydralazine's use and opens the door to repurposing it as part of a novel therapeutic strategy for brain cancer. The researchers emphasize that this is just the beginning. The next step involves designing new, more refined ADO inhibitors. The goal is to create drugs that are more tissue-specific and better at crossing the blood-brain barrier to target tumors precisely while minimizing effects on the rest of the body.

As Matthews points out, understanding the mechanics of long-known treatments like hydralazine is key to engineering the next generation of medical solutions. "It's rare that an old cardiovascular drug ends up teaching us something new about the brain," she says, highlighting the potential for other "unusual links" to yield new solutions for complex diseases.

The resolution of this 70-year-old puzzle demonstrates the immense value of basic scientific research in elucidating how our medicines work. By uncovering the shared vulnerability between preeclampsia and glioblastoma—a cellular oxygen alarm system—researchers have not only explained the past but have also charted a promising course for future treatments, offering new hope in two critical areas of human health.