Rethinking Dopamine: From Movement's Gas Pedal to Essential Engine Oil

A groundbreaking study from McGill University is challenging a fundamental neuroscience belief about dopamine's role in movement. New research published in Nature Neuroscience suggests dopamine does not act as a direct controller of movement speed or strength, but rather as a permissive background enabler—akin to oil in an engine. This paradigm shift, discovered through real-time monitoring in mice, reveals that restoring baseline dopamine levels, not manipulating rapid bursts during motion, is key to improving movement. The findings could fundamentally reshape the understanding and treatment of Parkinson's disease, potentially leading to simpler and more targeted therapeutic strategies.

For decades, neuroscience has operated under a compelling metaphor: dopamine as the brain's "gas pedal" for movement. This model suggested that rapid bursts of this neurotransmitter directly controlled the speed, force, and vigor of our actions. A landmark new study, however, is forcing a complete rethink. Published in Nature Neuroscience by researchers at McGill University, the research reveals dopamine's true role is far more foundational and subtle. Instead of a throttle, it functions as the essential "engine oil" that allows the motor system to run smoothly in the first place. This discovery not only rewrites a chapter in basic neuroscience but carries profound implications for how we understand and treat Parkinson's disease, a condition defined by dopamine loss.

The Paradigm Shift: From Throttle to Lubricant

The traditional view of dopamine in movement control gained traction with the advent of advanced brain-monitoring technologies. Scientists observed brief, subsecond spikes of dopamine occurring precisely as movements were initiated. It was a logical leap to conclude these bursts were the direct signals commanding action intensity. The new research, led by senior author Nicolas Tritsch, directly tested this assumption. "Our findings suggest we should rethink dopamine's role in movement," Tritsch stated. The study's core insight is that dopamine does not specify the "how" of movement—its speed or force—but rather the "if," creating the permissive conditions necessary for movement to occur at all.

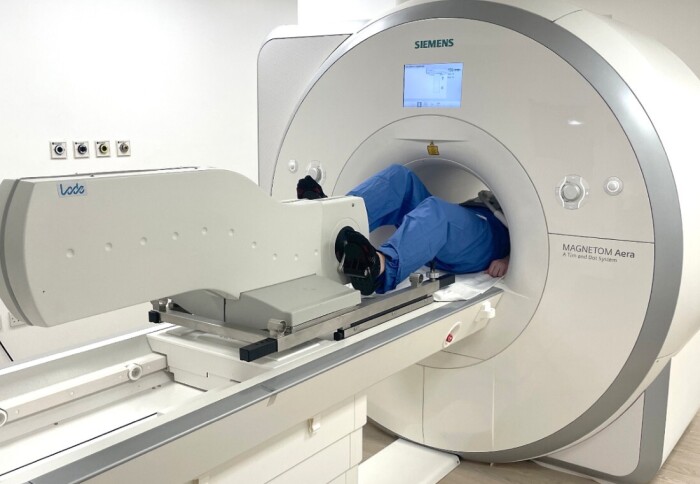

How the Discovery Was Made

The research team employed a sophisticated light-based technique to monitor and manipulate dopamine-producing neurons in the midbrains of mice in real time. The animals were trained to press a weighted lever, a task requiring motor vigor. Crucially, scientists could switch these dopamine cells "on" or "off" with precise timing during the movement itself. If the old gas-pedal model were correct, altering dopamine at the moment of action should have immediately changed how fast or hard the mice pressed the lever. The result was definitive: manipulating dopamine activity during the movement made no difference to its execution. The critical factor was the overall, baseline level of dopamine available to the system.

Implications for Parkinson's Disease and Treatment

This revised understanding directly impacts our comprehension of Parkinson's disease, a neurodegenerative disorder where the progressive loss of dopamine-producing neurons leads to slowness of movement (bradykinesia), tremors, and rigidity. The most common and effective treatment, levodopa, works by boosting dopamine levels in the brain. The new study clarifies why it works. The researchers found that levodopa improved movement not by restoring the short-lived dopamine bursts, but by raising the brain's overall dopamine tone back to a functional baseline. "Restoring dopamine to a normal level may be enough to improve movement. That could simplify how we think about Parkinson's treatment," explained Tritsch.

Toward the Future of Parkinson's Care

With over 110,000 Canadians living with Parkinson's—a number projected to more than double by 2050—this insight is urgently relevant. It suggests future therapeutic strategies should focus on maintaining steady, optimal levels of dopamine, rather than attempting to precisely mimic or control rapid signaling. This could lead to the development of safer, more targeted treatments. For instance, older dopamine receptor agonists, which often caused significant side effects by acting broadly in the brain, might be re-evaluated or redesigned with this new "engine oil" principle in mind, aiming for more sustained and precise modulation.

The McGill University study, "Subsecond dopamine fluctuations do not specify the vigor of ongoing actions," published in Nature Neuroscience, represents a significant correction to a long-held neuroscientific belief. By redefining dopamine from a direct commander to an essential facilitator, it provides a clearer, more accurate framework for understanding motor control. For the millions affected by Parkinson's disease worldwide, this shift from seeking a complex "throttle" to maintaining simple "engine oil" levels offers a promising new direction for research and a hopeful path toward more effective and manageable treatments. The brain's motor system, it turns out, doesn't need a frantic foot on the pedal; it needs the right conditions to run smoothly on its own.