Original Antigenic Sin: How Childhood Flu Infections Shape Lifelong Immunity

Original antigenic sin (OAS), also known as immune imprinting, is a fascinating phenomenon where our earliest childhood encounters with influenza viruses dictate our immune responses for life. This immunological memory shapes how we respond to flu infections and vaccinations throughout adulthood, offering both protection and potential vulnerabilities. Researchers are now studying this phenomenon through longitudinal studies like DIVINCI to understand its biological basis and implications for vaccine design. The concept explains why birth year can predict susceptibility to certain flu strains and why universal flu vaccines might need to overcome this deeply ingrained immune bias.

The human immune system possesses an extraordinary memory, but when it comes to influenza, this memory can be both a blessing and a curse. Original antigenic sin (OAS), a term coined in the 1950s, describes a phenomenon where our earliest childhood exposures to flu viruses create a lasting immunological imprint that shapes our responses to all subsequent flu encounters. This lifelong bias means the antibodies circulating in our blood decades later often match whichever influenza strains were most prevalent during our formative years, a discovery that has profound implications for public health, vaccine development, and our understanding of infectious disease.

What Is Original Antigenic Sin?

Original antigenic sin, increasingly referred to as immune imprinting, is the tendency of the immune system to preferentially boost antibody responses against influenza strains encountered in early childhood, even when exposed to newer, different strains later in life. The term originates from research in the 1950s that recognized most flu-binding antibodies in adults matched strains from their childhood. As explained by Scott Hensley, a microbiologist at the University of Pennsylvania, "Our earliest childhood exposures with influenza viruses prime antibody responses that last a lifetime." This imprinting affects the entire immune system, not just antibody levels, creating a foundational immune memory that persists for decades.

The Protective Power of Immune Imprinting

This phenomenon isn't necessarily detrimental. In fact, immune imprinting can provide significant protection against certain flu strains. A landmark 2016 study demonstrated this protective effect by correlating people's birth years with their susceptibility to emerging avian influenza subtypes. Researchers found that people whose earliest exposure came from a group 1 virus (containing H1, H2, or H5 haemagglutinin) had greater protection against the group 1 virus H5N1 later in life. Conversely, those imprinted with group 2 viruses (containing H3 or H7) were better protected against H7N9.

The protective mechanism involves circulating antibodies that can block the flu virus from infecting cells. Studies have shown that people born before 1968—likely imprinted with a group 1 virus—carry the highest levels of antibodies that can neutralize H5N1 strains. This has practical implications for pandemic planning: during an H5N1 outbreak, public health officials might prioritize vaccinating children over older adults, since older adults already have high levels of protective antibodies from childhood imprinting, while children start from a much lower baseline.

The Biological Basis: Memory B Cells and Competition

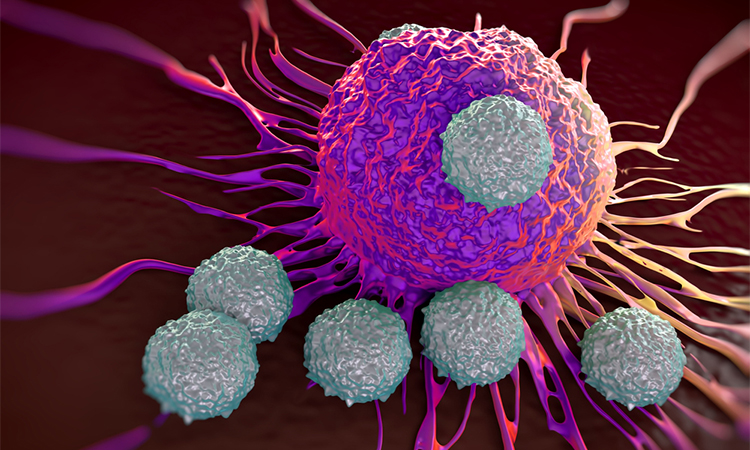

The immunological foundation of imprinting lies in memory B cells, which remember specific 3D features of influenza proteins called epitopes. When re-exposed to similar flu strains, these memory cells reactivate efficiently, producing antibodies rapidly. However, influenza's constantly shifting epitope landscape creates complications. Memory B cells might respond so efficiently that newly exposed, naive B cells miss their chance to engage with new or altered epitopes, potentially limiting the immune system's ability to adapt to viral evolution.

Animal studies provide insight into this competition. Research from Gabriel Victora's team at Rockefeller University showed that when mice are exposed to two identical or very similar flu strains in sequence, up to 90% of the antibody response comes from memory B cells. However, when the second exposure involves a haemagglutinin that's only 90% identical to the first, the response becomes more balanced between memory and naive B cells. As similarity decreases further, naive B cells contribute more significantly to the response.

The Potential Downsides and Vulnerabilities

While imprinting offers protection, it can also create vulnerabilities. The quality and target of imprinted antibodies matter significantly. If memory B cells produce antibodies targeting conserved, neutralizing parts of the virus, imprinting is protective. However, if they target non-essential viral regions, or if their focus becomes too narrow, protection may be compromised.

This vulnerability became apparent during specific flu seasons. For instance, people born in the 1960s and 1970s who were imprinted against a specific region of H1N1 showed increased susceptibility to a new H1N1 strain that emerged with a mutation in that exact region during the 2013-2014 flu season. Similarly, evidence suggests the same birth cohort in the United States and Canada experienced reduced vaccine effectiveness during the 2015-2016 season, possibly because their immune imprinting made it harder to generate immunity to that year's vaccine strain.

Research and Future Directions

Longitudinal studies like the Dissection of Influenza Vaccination and Infection for Childhood Immunity (DIVINCI) study are crucial for understanding imprinting's long-term effects. Following thousands of children from birth in the United States, Nicaragua, and New Zealand, researchers like Paul Thomas at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center aim to describe how immune responses form and how they function in downstream infections or vaccine scenarios. These studies face funding challenges, particularly for international sites, but their data could revolutionize flu vaccine design.

The ultimate goal is to harness or overcome OAS through better vaccines. Researchers are developing multivalent mRNA vaccines that induce immunity to multiple influenza haemagglutinins simultaneously. Scott Hensley's team has designed an mRNA vaccine that protects animals from H1N1 infections by targeting all 18 known influenza A haemagglutinins plus two influenza B haemagglutinins. Early research suggests mRNA vaccines might overcome OAS by generating prolonged immune responses that give naive B cells sufficient exposure to viral antigens, regardless of memory B cell activity.

As research continues, scientists are asking fundamental questions about immune memory: Is it better to have a broad initial imprint or a strong, focused one? The answers will shape the next generation of flu vaccines and our approach to seasonal and pandemic influenza preparedness for decades to come.