Capturing the Moment: How New Imaging Reveals the Dynamic Dance of Opioid Drugs

A groundbreaking study published in Nature uses time-resolved cryo-electron microscopy to capture fleeting, non-equilibrium states of the μ-opioid receptor (MOR) as it activates signaling proteins. The research visualizes how drugs with different efficacies—partial, full, and super-agonists—dynamically influence the receptor's shape and stability during the activation process. This work provides unprecedented structural insights into the molecular mechanisms of drug action, potentially paving the way for designing safer, more effective pain medications with fewer side effects.

Understanding how drugs work at the molecular level is a fundamental challenge in pharmacology. For medications targeting G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) like the μ-opioid receptor (MOR), a key question persists: why do different drugs binding to the same receptor produce varying strengths of cellular signaling? A landmark study published in Nature has now captured dynamic, high-resolution "snapshots" of this very process, offering a new window into the mechanics of drug efficacy. By employing an advanced imaging technique, researchers have visualized how ligands of differing potency physically manipulate the receptor in real-time, providing critical insights that could inform the future of drug design, particularly for pain management.

The Challenge of Capturing a Moving Target

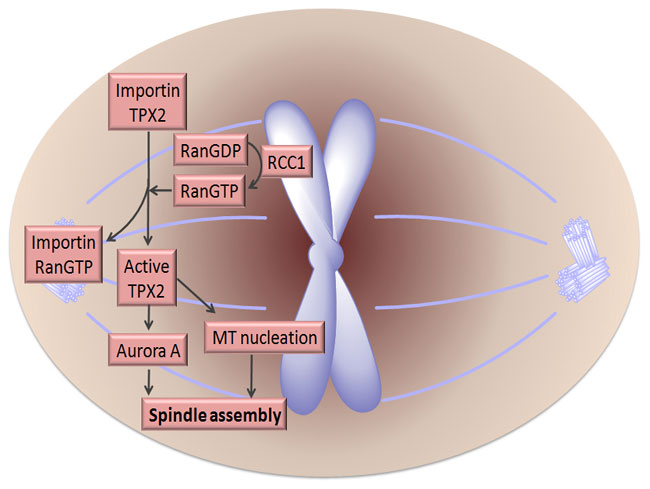

GPCRs like the MOR are not static locks waiting for a drug key. They are dynamic proteins that change shape to transmit signals inside the cell. Traditional structural biology methods often capture these proteins in stable, endpoint states, missing the crucial intermediate steps that define how effectively a signal is transmitted. This gap in understanding is significant for opioid drugs, where the difference between a partial agonist (producing a sub-maximal response) and a full or super-agonist is tied to clinical outcomes, efficacy, and side effect profiles. The research team hypothesized that these differences in signaling efficacy, or "ligand efficacy," could be structurally observed in the transient, non-equilibrium states the receptor adopts during activation.

A Time-Resolved Structural Approach

To test their hypothesis, the scientists utilized a sophisticated technique known as time-resolved cryo-electron microscopy (TR cryo-EM). This method allows researchers to freeze biological processes at millisecond intervals, effectively creating a molecular movie from a series of ultra-high-resolution still images. As detailed in the Nature publication, the team applied this approach to the MOR while it was bound to one of three different ligands and in the process of activating its intracellular partner, the Gαiβγ protein (Gi protein). The ligands represented a spectrum of efficacy: a partial agonist, a full agonist, and a super-agonist.

Key Findings: Ligand Efficacy in Motion

The TR cryo-EM data yielded an ensemble of conformational states along the G-protein activation pathway. One of the most significant discoveries was the resolution of a previously unobserved intermediate state. This vantage point allowed the team to directly visualize how receptor dynamics changed based on the bound ligand. The analysis revealed clear ligand-dependent differences:

- State Occupancy and Stability: Ligands with higher efficacy (full and super-agonists) promoted different distributions and stabilities of the receptor's conformational states compared to the partial agonist.

- Helical Dynamics: A strong correlation was found between higher ligand efficacy and increased dynamics, or movement, in the receptor's transmembrane helices 5 and 6 (TM5 and TM6). These helices are known to undergo major rearrangements during activation, and the study shows that more efficacious drugs induce a more dynamic, perhaps more "prepared," state in these critical regions.

- The "Kinetic Trap" Hypothesis: The data suggest that partial agonists may create a "kinetic trap" during G-protein activation. This implies that the receptor bound to a partial agonist gets transiently stuck in a less productive intermediate state, explaining its reduced signaling output compared to full agonists.

Broader Implications and Future Directions

Beyond opioid pharmacology, the study identified fundamental mechanistic differences in how the Gi protein (inhibitory) is activated by GTP compared to the Gs protein (stimulatory), likely explaining their distinct activation speeds in cells. These findings were corroborated by molecular dynamics simulations and single-molecule fluorescence assays, providing a multi-technique validation of the structural observations. Collectively, this work maps a dynamic structural landscape of GPCR-G-protein interactions. For drug discovery, especially in the critical field of pain management, this research provides a new framework. By understanding the specific receptor dynamics that lead to effective signaling versus side effects, scientists can aim to design novel ligands that are "biased" toward producing therapeutic benefits while minimizing adverse outcomes, potentially leading to a new generation of safer and more effective analgesics.