A New Twist in G-Protein Signaling Paves the Way for Next-Generation Opioids

Recent groundbreaking research published in Nature reveals unexpected behaviors in G proteins, a Nobel Prize-winning family of signaling proteins. This discovery challenges long-held scientific assumptions and opens a novel pathway for designing next-generation opioid drugs. By exploiting a newly identified 'GTP release-selective' mechanism, scientists aim to create analgesics that provide stronger, longer-lasting pain relief with potentially fewer side effects, marking a significant shift in rational drug design for pain management.

For decades, G proteins have been considered a well-understood cornerstone of cellular communication, a status cemented by the Nobel Prize awarded for their discovery. However, a pair of recent studies has turned this assumption on its head, revealing a previously unknown nuance in their signaling behavior. This unexpected twist is not merely an academic curiosity; it holds the potential to revolutionize the design of opioid painkillers. By targeting this newly uncovered mechanism, researchers envision a future of 'next-generation' opioids that offer superior, prolonged analgesic efficacy while potentially mitigating the severe side effects—like addiction and respiratory depression—that plague current treatments.

The G-Protein Signaling Revolution: From Nobel Prize to New Discovery

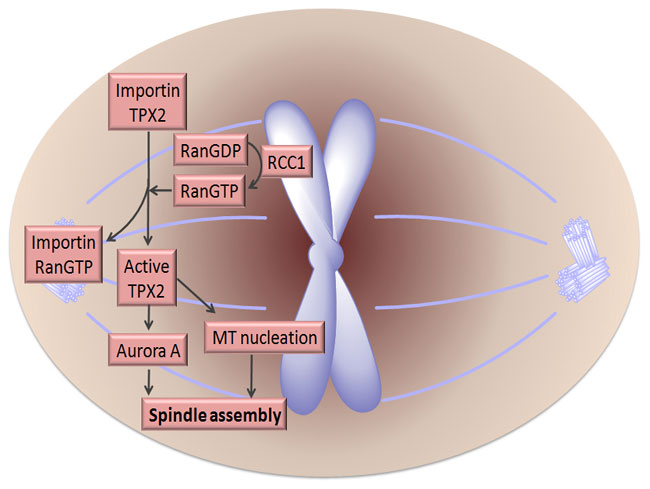

G proteins, or guanine nucleotide-binding proteins, act as crucial molecular switches inside cells, relaying signals from the outside—like hormones or drugs—to trigger internal responses. The canonical understanding involves a cycle where the G protein is activated by releasing a molecule called GDP and binding another, GTP. This 'GTP-bound' state then interacts with other proteins to propagate the signal before the G protein's own enzymatic activity eventually hydrolyzes GTP back to GDP, turning the signal off. This fundamental cycle has been the target of over 40% of all modern pharmaceuticals, including opioids which act through G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs).

The new research, led by Stahl et al. and published in Nature, introduces a critical refinement to this model. The studies demonstrate that the initial release of GDP from the G protein is not a single, uniform event but can be selectively influenced by different drugs binding to the receptor. This means a drug can be designed to be 'GTP release-selective,' preferentially promoting the sustained, active GTP-bound state of the G protein. This prolonged activation is directly linked to stronger and longer-lasting pain relief, as detailed in the companion paper in Nature Communications.

Implications for Next-Generation Opioid Design

The practical application of this discovery lies in the realm of 'biased signaling' or 'functional selectivity.' Traditional opioids like morphine activate a broad range of signaling pathways downstream of the mu-opioid receptor, including both the G protein pathway (associated with pain relief) and the beta-arrestin pathway (strongly linked to side effects like respiratory depression and constipation). The goal for decades has been to design drugs that favor the G protein pathway.

The GTP release-selectivity mechanism provides a new, more precise tool for achieving this. By creating opioid molecules that are exceptionally efficient at promoting and maintaining the GTP-bound state of the specific G protein subtype (Gαi) linked to analgesia, drug developers could theoretically maximize therapeutic benefit. As highlighted in the Nature News & Views article, this approach could lead to opioids where a single dose provides relief for a significantly extended period, reducing dosing frequency and potentially improving patient compliance and safety.

The Path Forward and Remaining Challenges

While the discovery is promising, translating it from a molecular mechanism to a safe, effective medicine involves significant hurdles. Researchers must now use this knowledge to rationally design and synthesize new chemical compounds that exhibit this selective property. These candidates will then undergo rigorous preclinical and clinical testing to confirm their efficacy and, crucially, their improved safety profile compared to existing opioids. The field will also need to investigate whether prolonging G protein signaling through this mechanism could have unforeseen cellular consequences with long-term use.

Nevertheless, this research represents a paradigm shift. It moves beyond simply trying to avoid the beta-arrestin pathway and instead focuses on actively optimizing the desired G protein signal. It underscores that even in well-trodden areas of biology, fundamental discoveries can still emerge, offering new hope for addressing some of medicine's most persistent challenges, such as the opioid crisis and the need for effective non-addictive pain management.