Rethinking Titan: New Study Suggests a Slushy Interior Instead of a Global Ocean

A new analysis of Cassini spacecraft data is challenging the long-held belief that Saturn's moon Titan harbors a vast, global subsurface ocean. Researchers from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory propose that Titan's interior may instead consist of deep layers of ice and slush, with isolated pockets of liquid water. This revised model, while still potentially habitable, suggests a more complex and evolving hydrosphere. The findings, published in Nature, highlight the dynamic nature of planetary science and set the stage for future exploration by missions like NASA's upcoming Dragonfly.

For over a decade, Saturn's enigmatic moon Titan has been classified among the solar system's "ocean worlds," believed to conceal a vast, global sea beneath its icy crust. This assumption, built on data from NASA's Cassini mission, painted Titan as a prime candidate in the search for extraterrestrial life. However, a groundbreaking new study is now challenging this paradigm, suggesting Titan's interior may be a slushy, partially frozen realm more akin to Earth's polar seas than a deep, buried ocean.

Revisiting Cassini's Data

The research, led by scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and published in the journal Nature, took a fresh look at observations made by the Cassini spacecraft. By applying improved data processing techniques, the team re-examined how Titan's surface responds to Saturn's immense gravitational pull. As Titan orbits Saturn, the planet's gravity causes the moon's surface to bulge. The timing and nature of this deformation can reveal crucial details about the moon's internal structure.

Lead author Flavio Petricca explained the key finding: if Titan contained a global, liquid-water ocean, the gravitational tug from Saturn would cause an immediate surface response. Instead, the team detected a 15-hour delay between the peak gravitational force and the corresponding bulge on Titan's surface. "This gap indicates an interior of slushy ice with pockets of liquid water," Petricca stated, a structure that would deform more slowly than a freely flowing ocean.

A Model of Ice, Slush, and Water

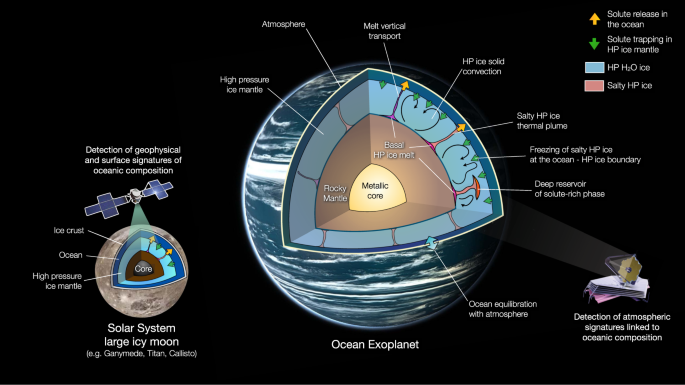

The new computer models propose a radically different internal architecture for Titan. Rather than a single, connected ocean, the moon may possess a complex, layered hydrosphere extending more than 340 miles (550 kilometers) deep.

- Outer Ice Shell: A rigid layer estimated to be about 100 miles (170 kilometers) thick.

- Intermediate Slush Layer: Beneath the ice, a vast region of partially melted ice and water.

- Pockets of Liquid Water: Within the slush, isolated reservoirs of liquid water that could extend another 250 miles (400 kilometers) downward, with temperatures potentially as warm as 68°F (20°C).

The study suggests Titan's internal water may be in a state of transition. Petricca noted that Titan's ocean may have frozen in the past and is currently melting, or its entire hydrosphere might be slowly evolving toward complete freezing. This dynamic picture contrasts with the more static view of a stable, global ocean.

Implications for Habitability and Scientific Debate

While this new model disputes the existence of a global ocean, it does not eliminate Titan's potential for habitability. The presence of warm, liquid water pockets within a slushy matrix could still provide niches where life might survive. Baptiste Journaux of the University of Washington, a co-author of the study, expressed continued optimism: "There is strong justification for continued optimism regarding the potential for extraterrestrial life." He added that "nature has repeatedly demonstrated far greater creativity than the most imaginative scientists" when it comes to the forms life can take.

However, the new theory is not without its skeptics. Luciano Iess of Sapienza University of Rome, whose earlier work using Cassini data supported the ocean hypothesis, finds the latest findings "certainly intriguing" but not yet conclusive. In an email, he stated that the evidence is "certainly not sufficient to exclude Titan from the family of ocean worlds," indicating that the scientific debate is far from settled.

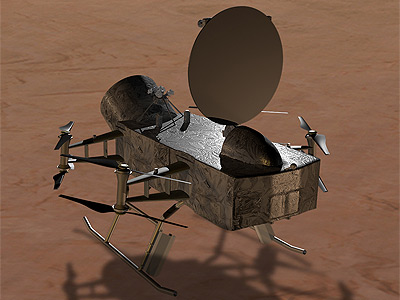

The Path Forward: Dragonfly and Beyond

The definitive answers may come from NASA's upcoming Dragonfly mission. Scheduled to launch later this decade, this revolutionary mission will send a helicopter-like rotorcraft to Titan's surface. By sampling materials and studying Titan's geology and atmosphere in situ, Dragonfly is expected to provide unprecedented insights into the moon's composition and internal structure. Baptiste Journaux is also a part of the Dragonfly science team, bridging this latest research with future exploration.

This study underscores the evolving nature of planetary science. As noted in the PBS NewsHour report, the Cassini mission, which ended in 2017, continues to yield new discoveries through advanced re-analysis of its data. Titan remains a world of profound mystery, whether it hosts a global ocean or a slushy interior. Its lakes of liquid methane on the surface and the potential for liquid water below ensure it will remain a high-priority target for astrobiologists and planetary scientists for decades to come.