Island Spider Defies Evolution: Genome Halved While Genetic Diversity Grows

In a groundbreaking discovery that challenges long-held evolutionary theories, scientists have found that the spider species Dysdera tilosensis on the Canary Islands has reduced its genome size by nearly 50% while simultaneously increasing its genetic diversity. This unexpected finding contradicts traditional assumptions that island species develop larger, more repetitive genomes. The research, published in Molecular Biology and Evolution, reveals how this spider accomplished this remarkable genetic transformation in just a few million years, providing new insights into how isolation shapes evolutionary processes.

In a remarkable discovery that challenges fundamental evolutionary principles, scientists have uncovered an extraordinary genetic phenomenon on the Canary Islands. The spider species Dysdera tilosensis has accomplished what was previously thought impossible: reducing its genome size by nearly half while simultaneously increasing its genetic diversity. This finding, published in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, overturns long-standing assumptions about how isolation affects genome evolution.

Challenging Evolutionary Dogma

Traditional evolutionary theory has long maintained that species colonizing islands tend to develop larger genomes with more repetitive DNA. This assumption stems from the founder effect, where small populations establishing themselves in new environments experience reduced selective pressure, allowing for the accumulation of genetic material. However, the University of Barcelona-led research team discovered precisely the opposite pattern in the island spider Dysdera tilosensis.

The study compared two closely related spider species: Dysdera catalonica from mainland Europe and D. tilosensis from Gran Canaria. While D. catalonica possesses a genome of 3.3 billion base pairs, D. tilosensis has dramatically reduced its genetic material to just 1.7 billion base pairs. Despite this nearly 50% reduction, the island species exhibits greater genetic diversity than its mainland relative.

The Canary Islands Evolutionary Laboratory

The Canary Islands have long served as a natural laboratory for studying evolution in isolation. The archipelago's unique geological history and isolation have facilitated remarkable diversification among various species. Spiders of the genus Dysdera have been particularly successful in this environment, with nearly 50 endemic species evolving since the islands emerged millions of years ago.

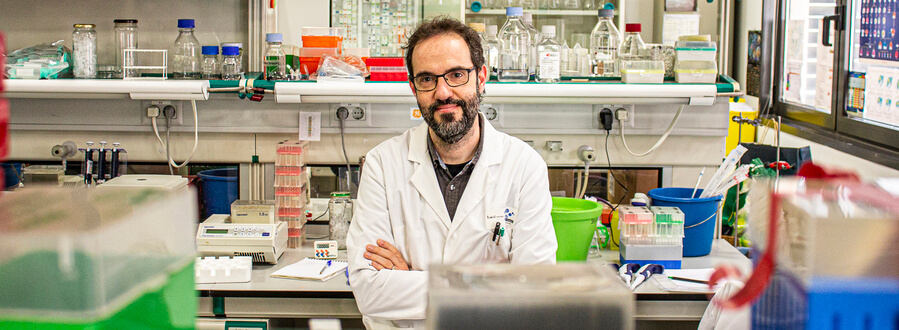

Professor Julio Rozas, director of the Evolutionary Genomics and Bioinformatics research group at the University of Barcelona, explains the significance of this discovery: "The genome downsizing of the spider D. tilosensis, associated with the colonization process of the Canary Island, is one of the first documented cases of drastic genome downsizing using high-quality reference genomes. This phenomenon is now being described for the first time in detail for phylogenetically closely related animal species."

Implications for Evolutionary Biology

This discovery has profound implications for understanding how genome size evolves in isolated populations. The research suggests that rather than direct adaptation to environmental conditions, genome size changes may result from a balance between the accumulation of repetitive DNA elements and their removal through natural selection.

Doctoral student Vadim Pisarenco, the study's first author, notes the paradoxical nature of their findings: "In the study, we observed the opposite of what theories predicted: island species have smaller, more compact genomes with greater genetic diversity. This pattern suggests the presence of non-adaptive mechanisms, whereby populations in the Canary Islands would have remained relatively numerous and stable for a long time."

The research team proposes that stable population sizes on the islands maintained strong selective pressure, enabling the elimination of unnecessary DNA while preserving genetic diversity. This challenges the conventional wisdom that island colonization necessarily leads to genetic bottlenecks and reduced diversity.

As scientists continue to unravel the mysteries of genome evolution, this unexpected discovery in the Canary Islands serves as a powerful reminder that nature often defies our expectations. The humble island spider has rewritten evolutionary rules, demonstrating that genetic complexity doesn't always correlate with genome size and that isolation can drive innovation in unexpected ways.