How Methane-Producing Gut Microbes May Influence Calorie Absorption

Arizona State University researchers have discovered that methane-producing microbes in the human gut may significantly impact how many calories individuals extract from fiber-rich foods. The study reveals that people whose gut microbiomes generate more methane tend to absorb more energy from high-fiber diets, suggesting that individual microbial composition plays a crucial role in digestion efficiency. This groundbreaking research, conducted using advanced metabolic chambers, could pave the way for personalized nutrition approaches tailored to each person's unique gut microbiome.

Groundbreaking research from Arizona State University reveals that methane-producing microbes in our gut may play a surprising role in determining how many calories we extract from our food. This discovery challenges conventional understanding of digestion and opens new possibilities for personalized nutrition approaches based on individual microbial composition.

The Methane-Microbiome Connection

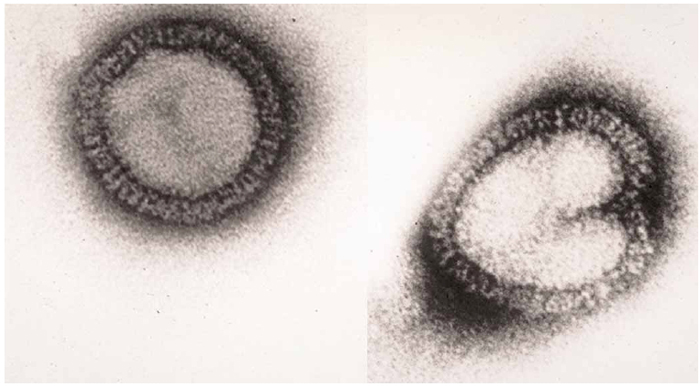

According to the ASU study published in The ISME Journal, people whose gut microbiomes produce higher levels of methane tend to extract significantly more calories from fiber-rich foods. The research team, led by graduate researcher Blake Dirks, identified methane-producing microorganisms called methanogens as key players in this digestive efficiency phenomenon.

These methanogens function as hydrogen consumers within the gut ecosystem. When other microbes ferment dietary fiber into short-chain fatty acids—valuable energy sources for the body—they release hydrogen gas as a byproduct. Methanogens then consume this hydrogen, producing methane in the process and maintaining the delicate chemical balance necessary for efficient digestion.

Advanced Research Methodology

The ASU researchers employed sophisticated whole-room calorimeters to conduct their investigation. Participants spent six days in these sealed, hotel-like environments while following two distinct diets: one featuring highly processed, low-fiber foods and another emphasizing whole foods and fiber-rich options. Both diets contained identical proportions of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats.

This advanced methodology allowed researchers to continuously monitor methane production through both breath and other emissions, providing a comprehensive view of microbial activity that traditional single breath tests cannot capture. The collaboration between ASU's microbial ecology experts and clinical-translational scientists from the AdventHealth Translational Research Institute enabled precise measurement of energy balance and microbial function.

Implications for Personalized Nutrition

The findings suggest that gut methane levels could serve as a biomarker for digestive efficiency. "The human body itself doesn't make methane, only the microbes do. So we suggested it can be a biomarker that signals efficient microbial production of short-chain fatty acids," explains Rosy Krajmalnik-Brown, corresponding author of the study and director of the Biodesign Center for Health Through Microbiomes.

While all participants absorbed fewer calories on the high-fiber diet compared to the processed-food diet, those with higher methane production consistently extracted more energy from fiber-rich foods. This variation highlights the importance of personalized approaches to nutrition, as the same carefully designed diet produced different effects based on individual microbial composition.

Future Research Directions

The study lays important groundwork for future investigations into how methanogens might influence weight management and specialized nutrition programs. Although the research focused on relatively healthy participants, the team anticipates exploring how different populations—including those with obesity, diabetes, or other health conditions—respond to various dietary interventions based on their microbial profiles.

This research represents a significant step toward understanding how individual differences in gut microbiome composition affect nutritional outcomes. As personalized medicine continues to evolve, insights from studies like this one may eventually enable healthcare providers to design dietary recommendations tailored to each person's unique microbial ecosystem.