Unmasking Cancer: How MIT and Stanford's Sugar-Shield Breakthrough Supercharges Immunotherapy

A groundbreaking new therapy developed by scientists at MIT and Stanford University promises to make cancer immunotherapy effective for more patients. By targeting a hidden 'off switch'—special sugar molecules on tumor cells that suppress immune activity—the novel AbLec molecules strip cancer of its camouflage. This approach, detailed in Nature Biotechnology, combines antibody precision with lectin power to block glycan-based immune checkpoints, unleashing a potent anti-tumor response that has outperformed standard antibody treatments in early tests.

Cancer immunotherapy has revolutionized treatment by harnessing the body's own defenses, yet its success remains frustratingly limited. For many patients, tumors deploy clever evasive tactics, rendering these powerful therapies ineffective. Now, a collaborative breakthrough from researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Stanford University offers a promising new path. Their strategy targets a fundamental camouflage mechanism: special sugar molecules, or glycans, that act as a hidden "off switch" for the immune system. By developing innovative molecules that strip away this sugar shield, the scientists have unlocked a more potent immune attack, potentially expanding the reach of immunotherapy to countless more patients.

The Sugar Shield: Cancer's Invisibility Cloak

To understand this breakthrough, one must first grasp how cancer manipulates the immune system. A major advance in treatment came with checkpoint inhibitor drugs, which block proteins like PD-1 and PD-L1. This interaction acts as a brake, preventing immune cells like T cells from attacking. While these inhibitors have produced remarkable remissions, they fail for a significant portion of patients. This failure has driven the search for other immunosuppressive pathways tumors exploit.

The new research, published in Nature Biotechnology, zeroes in on a different class of brake: glycans. These sugar chains coat nearly all cells, but cancer cells often display unique versions rich in a sugar building block called sialic acid. When immune cells equipped with receptors called Siglecs encounter these sialic acids on a tumor, a dampening signal is triggered. "When Siglecs on immune cells bind to sialic acids on cancer cells, it puts the brakes on the immune response," explains lead author Jessica Stark, a professor at MIT's Koch Institute. This creates a "glyco-immune checkpoint," a sugar-based off switch that parallels the protein-based PD-1 pathway.

Engineering the Solution: The Birth of AbLecs

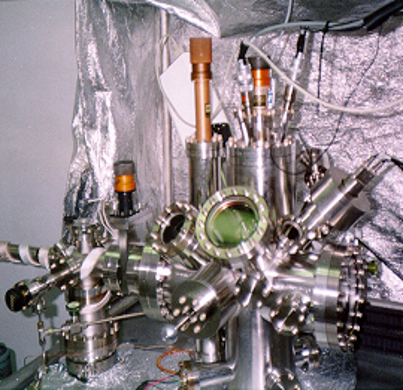

The scientific challenge was significant. While lectins—proteins that bind sugars—could theoretically block this interaction, they naturally bind too weakly to accumulate effectively on cancer cells. The MIT-Stanford team's ingenious solution was to fuse a lectin to a tumor-targeting antibody, creating a new class of molecule they call Antibody-Lectin chimeras, or AbLecs.

In this design, the antibody portion acts as a precision-guided delivery vehicle, homing in on specific proteins (antigens) abundant on cancer cells, such as HER2. Once anchored to the tumor, the attached lectin domain—engineered from human Siglec-7 or Siglec-9—binds densely to the sialic acids on the cancer cell surface. This action physically blocks the sugars from engaging the Siglec receptors on patrolling immune cells like macrophages and natural killer (NK) cells, thereby lifting the brake and unleashing their cytotoxic potential.

Promising Results and a Modular Future

Early experimental data is compelling. In laboratory cell cultures, AbLecs successfully reprogrammed immune cells, prompting them to attack and kill cancer cells. More importantly, in mouse models engineered with human immune receptors, treatment with an AbLec (using the breast cancer antibody trastuzumab) resulted in significantly fewer lung metastases compared to treatment with the antibody alone. This demonstrates a direct therapeutic enhancement beyond existing standards.

A key strength of the platform is its modular "plug-and-play" nature. Researchers showed they could swap the antibody component to target different cancers (e.g., using rituximab for CD20 or cetuximab for EGFR) and could also exchange the lectin domain to block other immunosuppressive glycans. This flexibility suggests the approach could be tailored to a wide array of cancers. "AbLecs are really plug-and-play... You can imagine swapping out different decoy receptor domains... and you can also swap out the antibody arm," Stark notes, highlighting its broad potential.

The Road Ahead: From Lab to Clinic

The translational path for this discovery is already underway. Stark and senior author Carolyn Bertozzi of Stanford have co-founded a company, Valora Therapeutics, to advance lead AbLec candidates toward clinical trials. The goal is to initiate human trials within the next two to three years. This move from academic insight to commercial development underscores the high confidence in the technology's therapeutic potential. The work was supported by numerous grants, including awards from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the National Cancer Institute, and the V Foundation.

This research represents a significant paradigm shift. By moving beyond protein checkpoints to target the sugary "glycocode" of cancer, it opens a new front in the war on tumors. If successful in clinical trials, AbLecs could provide a powerful new tool for oncologists, offering hope to patients for whom current immunotherapies have fallen short. It stands as a testament to the power of interdisciplinary collaboration, merging immunology, chemical biology, and engineering to outsmart one of medicine's most formidable foes.