Earth's Fiery Birth: How a Hidden Water Vault Saved Our Oceans

New research reveals how Earth's oceans survived the planet's molten infancy. Scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences discovered that bridgmanite, the most abundant mineral in Earth's mantle, can store vast quantities of water at extreme temperatures. This hidden reservoir, potentially holding water volumes comparable to today's oceans, remained safely underground during Earth's fiery early phase. As the planet cooled, this deep water helped drive geological processes and eventually resurfaced to create the habitable world we know today, solving a long-standing mystery about Earth's water origins.

For decades, planetary scientists have grappled with a fundamental mystery: how did Earth's vast oceans survive the planet's violent, molten birth? Around 4.6 billion years ago, Earth resembled a blazing furnace more than a blue marble, with surface temperatures so extreme that liquid water couldn't exist. Yet today, oceans cover 70% of our planet's surface. A groundbreaking study published in Science in December 2025 offers a compelling answer: water didn't escape to space—it went into hiding deep within the planet itself.

The Mineral That Saved Our Oceans

The key to this survival story lies in a mineral called bridgmanite, which forms the bulk of Earth's lower mantle. Previous research suggested this mineral could only hold minimal amounts of water, but those studies were conducted at relatively low temperatures. The new research, led by Prof. Zhixue Du of the Guangzhou Institute of Geochemistry, reveals that bridgmanite's water-storage capacity increases dramatically under the extreme heat conditions of early Earth.

Using advanced experimental techniques, the researchers discovered that during Earth's hottest magma ocean phase, newly formed bridgmanite could have functioned as microscopic "water containers," trapping significant amounts of water as the planet solidified from molten rock. This finding challenges the long-standing assumption that Earth's lower mantle is almost completely dry.

Breakthrough Experimental Methods

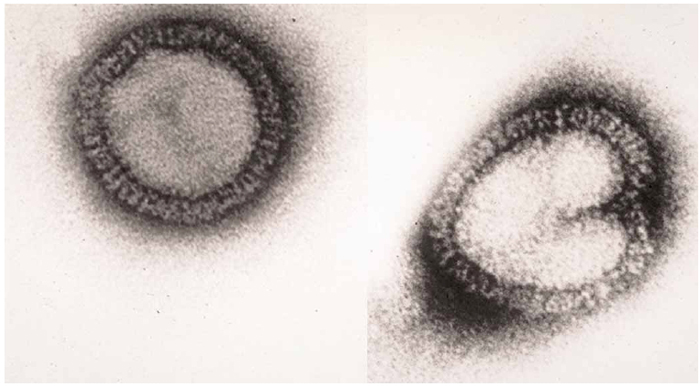

To test their hypothesis, the research team had to overcome significant technical challenges. They needed to recreate conditions found more than 660 kilometers beneath Earth's surface—pressures and temperatures so extreme they would vaporize most laboratory equipment. Their solution was a custom-built diamond anvil cell system combined with laser heating and high-temperature imaging, capable of reaching temperatures up to approximately 4,100°C.

The team employed sophisticated analytical techniques including cryogenic three-dimensional electron diffraction, NanoSIMS, and atom probe tomography. These methods acted like ultra-high-resolution "chemical CT scanners" and "mass spectrometers" for the microscopic world, allowing researchers to map water distribution within samples thinner than one-tenth the width of a human hair.

A Reservoir of Planetary Proportions

The experimental results were striking. The researchers found that bridgmanite's water partition coefficient—its ability to trap water—increases sharply at higher temperatures. Using these findings, they modeled Earth's magma ocean cooling and crystallization process. Their simulations suggest the lower mantle became the largest water reservoir within solid Earth after the magma ocean cooled, potentially holding between 0.08 to 1 times the volume of today's oceans.

This represents a reservoir five to 100 times larger than earlier estimates. The water wasn't merely stored passively—it played an active role in Earth's geological evolution. By lowering the melting point and viscosity of mantle rocks, this deeply stored water acted as a "lubricant" for Earth's internal engine, helping drive mantle circulation and plate tectonics.

From Inferno to Habitable World

Over geological timescales, this buried water slowly returned to the surface through volcanic and magmatic activity. This gradual release contributed to the formation of Earth's early atmosphere and oceans. The researchers suggest this process was crucial in transforming Earth from a molten inferno into the life-friendly planet we inhabit today.

The study, published as "Substantial water retained early in Earth’s deep mantle" in Science, represents a significant shift in our understanding of planetary evolution. It provides a plausible mechanism for how water—essential for life as we know it—endured Earth's most violent period. This research not only solves a long-standing puzzle about our own planet but may also inform our search for habitable worlds beyond our solar system, suggesting that water survival mechanisms might be more complex than previously imagined.