How Our Gut Bacteria Are Rapidly Evolving: New Research Reveals Widespread Adaptation

A groundbreaking study published in Nature reveals that human gut bacteria are undergoing pervasive, rapid evolution through a process called 'gene-specific selective sweeps.' Researchers developed a new statistical tool, the integrated linkage disequilibrium score (iLDS), to detect over 300 adaptive events across 30 prevalent gut species from 24 global populations. The findings strongly implicate host diet—particularly the shift to industrialized foods—as a critical selection pressure, with bacteria adapting to metabolize components like maltodextrin. This research uncovers the dynamic evolutionary landscape within our microbiome and its connection to modern lifestyle.

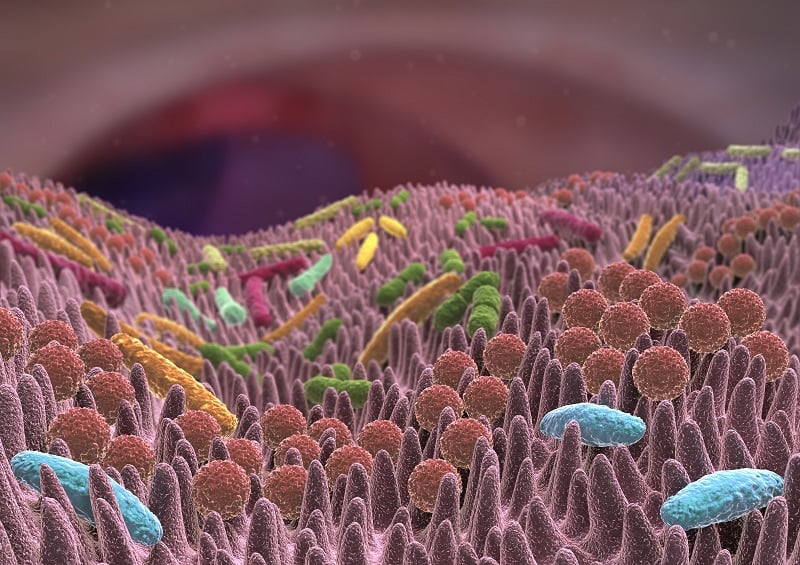

The trillions of bacteria residing in our gut are not static passengers; they are dynamic communities engaged in a continuous evolutionary arms race. A landmark study published in Nature in December 2025 has unveiled the startling scale and mechanism of this adaptation. By developing a novel analytical tool, researchers have detected hundreds of instances where beneficial genetic variants are sweeping through populations of human gut bacteria, a process driven by our changing diets and lifestyles. This research, detailed in the article "Gene-specific selective sweeps are pervasive across human gut microbiomes", provides unprecedented insight into how our internal microbial ecosystem evolves in real-time to meet environmental pressures.

Unlocking Evolutionary Secrets with the iLDS Statistic

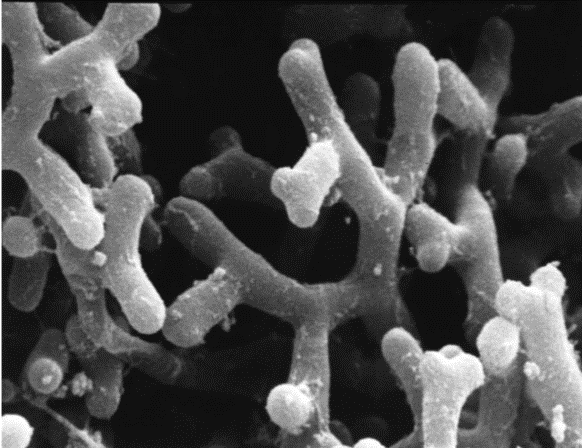

Detecting natural selection in fast-evolving bacterial communities is notoriously difficult. The research team, led by Nandita R. Garud, overcame this challenge by creating the integrated linkage disequilibrium score (iLDS). This sophisticated statistic is designed to identify "gene-specific selective sweeps"—scenarios where a beneficial genetic mutation rapidly increases in frequency within a population, carrying nearby "hitchhiking" DNA along with it. The iLDS works by comparing patterns of genetic linkage, specifically the correlation between variants at different genomic positions, for non-synonymous mutations (which change the protein) versus synonymous mutations (which do not).

As explained in the study, during a selective sweep, a genomic fragment containing an adaptive variant transfers between bacterial strains via horizontal gene transfer. This creates a distinct signature of elevated linkage disequilibrium around the beneficial gene. The iLDS is calibrated to spot this signature while controlling for other non-selective evolutionary forces, making it a powerful and conservative tool for pinpointing true adaptive events.

Pervasive Adaptation Across Global Populations

Applying the iLDS to data from 24 human populations worldwide revealed a stunning picture of constant microbial evolution. The analysis identified more than 300 selective sweeps across approximately 30 of the most prevalent commensal gut species. This indicates that recombination—the swapping of genetic material between strains—is a primary engine for spreading adaptive DNA in our guts.

The study analyzed both quasi-phased haplotypes from metagenomic samples of 693 people and a broader collection of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) and isolates. The results were consistent: selective sweeps are a common feature. On average, species showed evidence of multiple sweeps, with a median of four adaptive events detected per species. This pervasive adaptation suggests our gut bacteria are in a state of continuous evolutionary fine-tuning.

Diet as a Dominant Selective Force

A key finding from the research is the clear role of host diet as a major driver of microbial evolution. The genes identified as being under selection were significantly enriched for functions related to carbohydrate metabolism and transport. This points directly to adaptation to the nutrients we consume.

One of the most striking examples involves genes called mdxE and mdxF. These genes code for transporters that metabolize maltodextrin, a synthetic starch derivative widely used as an emulsifier in ultra-processed foods. The iLDS detected a selective sweep at this locus in species like Ruminococcus bromii and Eubacterium siraeum. Crucially, this adaptation was found in all 14 industrialized populations studied but was absent from non-industrialized populations, strongly suggesting it is an evolutionary response to a modern, processed diet.

The Industrialization Divide in Gut Evolution

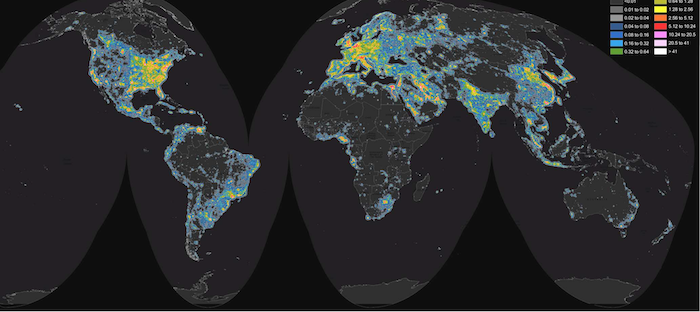

The study uncovered a significant evolutionary divergence between industrialized and non-industrialized human populations. While both groups exhibited a similar number of selective sweeps overall, the targets of adaptation were distinctly different.

Industrialized populations (from North America, Europe, and Asia) shared adaptive sweeps with each other more than twice as often as they did with non-industrialized populations (from Fiji, Madagascar, Peru, El Salvador, and Mongolia). This indicates that shared lifestyles, diets, and environments in industrialized societies are creating convergent evolutionary pressures on gut microbes. In contrast, non-industrialized populations harbor unique sweeps, likely reflecting adaptation to more traditional, region-specific diets and conditions.

Implications for Health and Future Research

The discovery of widespread, diet-driven evolution within the gut microbiome has profound implications. It suggests that shifts in human diet rapidly reshape not just which bacterial species are present, but also the genetic capabilities of the species that remain. This could influence everything from digestive efficiency to the microbiome's role in immune function and disease.

The researchers note that their use of iLDS was calibrated to be conservative, meaning the true extent of adaptive evolution is likely even greater. The hundreds of sweeps identified, spanning 447 genes, provide a rich roadmap for future study. Investigating the functional consequences of these selected variants could lead to a better understanding of how specific microbiome genotypes affect host health, potentially informing the development of targeted probiotics or dietary interventions.

In conclusion, this research transforms our view of the gut microbiome from a relatively stable ecosystem to a dynamic, evolving landscape. The bacteria within us are continuously adapting through recombination and selection, with our modern diet acting as a powerful evolutionary force. Understanding this ongoing co-evolution is a critical step toward harnessing the microbiome for improved human health.