How a Brain Protein Called KCC2 Secretly Accelerates Habit Formation

New research from Georgetown University reveals a hidden mechanism in the brain that explains why habits and cravings can form so quickly and powerfully. Scientists have discovered that fluctuations in a protein called KCC2 can dramatically reshape how our brains link everyday cues with rewards. When KCC2 levels drop, dopamine neurons fire more intensely, strengthening new associations in a process that mirrors how addictive behaviors take hold. This discovery offers crucial insights into the neural basis of habit formation and opens new avenues for understanding and treating conditions like addiction.

Have you ever wondered why a simple morning routine, like drinking coffee, can trigger an intense craving for a cigarette, or why checking your phone becomes an automatic response to a notification sound? The answer may lie in the subtle workings of a single brain protein. Groundbreaking research from Georgetown University Medical Center has uncovered a precise molecular mechanism that explains how everyday cues can secretly and powerfully shape our habits. The study, published in Nature Communications, focuses on a protein called KCC2 and its profound influence on the brain's reward-learning system.

This research provides a critical link between cellular biology and complex behavior. It reveals that the brain's ability to form associations is not static but can be dynamically tuned by molecular changes. Understanding this process is vital, as disrupted reward learning is a hallmark of numerous brain disorders, including addiction, depression, and schizophrenia. By pinpointing the role of KCC2, scientists are moving closer to deciphering why harmful habits can be so difficult to break and how healthy learning processes might be restored.

The KCC2 Protein: A Molecular Regulator of Learning

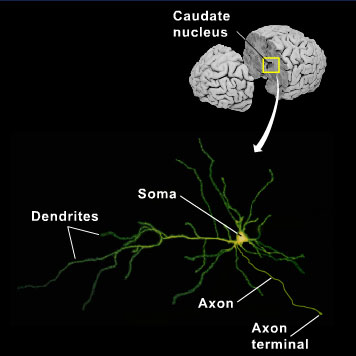

At the heart of this discovery is KCC2, a protein crucial for maintaining the proper balance of chloride ions in neurons. This ionic balance is fundamental for inhibitory signaling in the brain, which helps regulate overall neural excitability. The Georgetown team, led by Dr. Alexey Ostroumov, discovered that shifts in the levels of this protein can directly alter the brain's capacity for reward learning. "Our ability to link certain cues or stimuli with positive or rewarding experiences is a basic brain process, and it is disrupted in many conditions," explains Ostroumov.

The study's key finding is that when KCC2 levels are reduced, dopamine neurons in the midbrain fire more rapidly and intensely. Dopamine is the neurotransmitter famously associated with motivation, pleasure, and reinforcement learning. This amplified dopamine signal acts as a supercharged teaching signal for the brain, causing it to form new connections between a neutral cue (like a sound or a context) and a rewarding outcome (like sugar or a drug) much more quickly and robustly than under normal conditions.

From Rat Studies to Human Habits

To unravel this mechanism, the researchers employed a multifaceted approach, combining electrophysiology, pharmacology, fiber photometry, and behavioral tests. They used rats in classic Pavlovian conditioning experiments, where a brief sound signaled the delivery of a sugar reward. By monitoring the animals' brains and behavior, the team could directly observe how manipulating KCC2 affected learning speed and strength.

The research went beyond simple firing rates. The investigators discovered that neurons don't just fire more; they can fire in a coordinated, synchronized pattern. These brief, synchronized bursts of neural activity appear to be particularly effective at amplifying dopamine release, creating an exceptionally potent learning signal. This coordination helps the brain efficiently assign value and meaning to experiences, cementing the cue-reward association. This neural "chorus" may be why certain habits become deeply ingrained after only a few repetitions.

Implications for Addiction and Beyond

The implications of this research are far-reaching, particularly for understanding addiction. The process of reduced KCC2 leading to intensified dopamine bursts closely resembles how addictive substances are thought to hijack the brain's natural learning pathways. "For example, drug abuse can cause changes in the KCC2 protein that is crucial for normal learning. By interfering with this mechanism, addictive substances can hijack the learning process," states Ostroumov. This explains the classic example of a smoker developing an irresistible craving when encountering a cue like morning coffee, even long after quitting.

Furthermore, the study examined the effects of the benzodiazepine drug diazepam (Valium). The team found that such drugs can influence this coordinated neural activity, adding another layer to understanding how pharmaceuticals affect learning and memory circuits. This suggests that treatments targeting the KCC2 pathway or neural coordination could offer new strategies for disorders characterized by maladaptive learning.

A New Frontier in Brain Disorder Treatment

The discovery opens a promising new frontier in neuroscience and psychiatry. "We believe these discoveries extend beyond basic learning research," says Ostroumov. "They reveal new ways the brain regulates communication between neurons. And because this communication can go wrong in different brain disorders, our hope is that by preempting these disruptions, or by fixing normal communication when it's impaired, we can help develop better treatments for a wide range of brain disorders."

By identifying KCC2 as a key regulator of reward learning, this research provides a specific molecular target. Future therapies could aim to stabilize KCC2 levels to prevent the formation of harmful associations or to restore balanced learning in conditions where it has gone awry. This work, supported by the National Institutes of Health, fundamentally shifts our understanding of habit formation from a purely behavioral phenomenon to one with a clear, modifiable biological basis, offering hope for more effective interventions in the future.