SPHERE's Stunning Images Reveal the Hidden Machinery of Planet Formation

Astronomers using the SPHERE instrument on the Very Large Telescope have captured an unprecedented collection of images showing dusty debris disks around young stars. These detailed portraits offer a rare, direct glimpse into the chaotic environments where planets are born. The images reveal bright arcs, sharp edges, and faint clouds of dust—the telltale signs of colliding planetesimals and the gravitational influence of unseen, massive planets. This survey provides one of the most complete views yet of how solar systems evolve in their infancy, acting as a roadmap for discovering new worlds.

The birth of a planet is a violent, dusty affair, hidden from direct view by the blinding glare of its parent star. For decades, astronomers have theorized about this process, but direct observation remained a monumental challenge. Now, a breakthrough survey using the SPHERE instrument is pulling back the curtain. By capturing stunningly detailed images of debris disks—the dusty rings surrounding young stars—scientists are witnessing the hidden machinery of planet formation in action. These portraits are not just beautiful; they are astronomical treasure maps, revealing where worlds are being built and where to search for planets we have yet to discover.

Unveiling the Unseen: How SPHERE Peers Into Stellar Nurseries

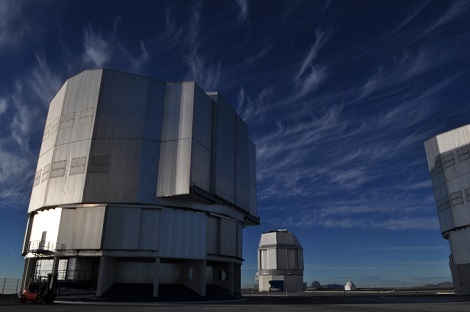

The fundamental challenge in imaging planets or the disks that form them is the overwhelming brightness of the central star. It’s akin to trying to photograph a speck of dust floating next to a blazing searchlight from miles away. The SPHERE instrument, operational since 2014 on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT), was engineered specifically to solve this problem. It employs a sophisticated coronagraph—essentially a small disk that blocks the star's direct light—much like shielding your eyes from the sun to see what's around it.

This feat requires extreme precision. SPHERE uses an advanced adaptive optics system that constantly measures and corrects for the distorting effects of Earth's atmosphere in real time, using a deformable mirror. Furthermore, it can filter for polarized light, which is characteristic of starlight scattered by dust grains, making the faint, wispy structures of debris disks stand out clearly against the dark backdrop of space. This technological marvel has enabled the direct imaging of features previously only inferred.

The Dusty Fingerprints of Planet Formation

The new study, led by Natalia Engler of ETH Zurich, processed data from 161 nearby young stars. The result is a unique catalog of 51 sharply resolved debris disks, four of which had never been imaged before. These are not the smooth, primordial disks of gas and dust from which planets initially coalesce. Instead, they are secondary debris disks—signs of a later, more violent stage of system evolution.

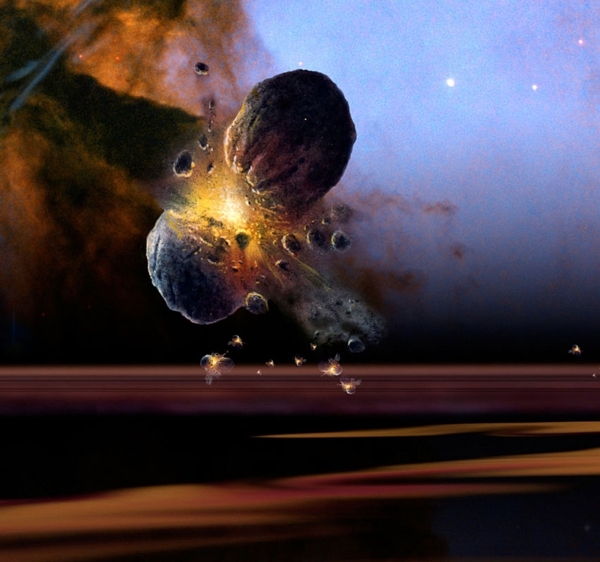

As Dr. Julien Milli, a co-author of the study, explains, directly detecting the small bodies—asteroids and comets—in these distant systems is "downright impossible." The breakthrough comes from observing the dust these bodies create. When planetesimals (the building blocks of planets) collide, they are shattered into countless microscopic dust grains. While the total volume of material remains the same, its surface area increases exponentially, making it vastly more reflective and detectable. By studying this dust, astronomers can infer the properties and activities of the unseen population of colliding bodies creating it.

Rings, Gaps, and the Hand of Hidden Planets

The SPHERE images reveal an astonishing diversity of structures. Many disks show distinct rings or belts, with material concentrated at specific distances from the star. This arrangement is strikingly familiar: it mirrors our own solar system's architecture, where small bodies are gathered in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter and the Kuiper belt beyond Neptune.

These patterns are not random. They are sculpted by gravity, most likely from massive, orbiting planets. As planets move through the disk, they clear paths, shepherd material into rings, and create sharp edges or gaps. In some of the imaged systems, planets have already been detected. In others, the disks' asymmetries and sharp boundaries serve as compelling indirect evidence for planets still waiting to be seen. Gaël Chauvin, project scientist for SPHERE, calls the dataset "an astronomical treasure" precisely because it allows such deductions about unseen components of planetary systems.

A Roadmap for Future Discovery

This comprehensive survey does more than provide snapshots of cosmic beauty; it creates a valuable target list for the next generation of observatories. The sharp edges and gaps seen in these dusty rings are like signposts pointing astronomers where to look. Upcoming powerful instruments, such as those on the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the future Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), will train their sights on these systems with the goal of directly imaging the planets responsible for sculpting the dust.

The research also uncovered broader trends: more massive young stars tend to host more massive debris disks, and disks with dust concentrated farther from the star also show greater mass. These correlations help refine models of how planetary systems form and evolve across the galaxy. By comparing these young, active disks to the faint, aged remnants in our own solar system—the zodiacal light and the distant Kuiper belt—scientists can trace the full lifecycle of a solar system from its chaotic birth to its quiet maturity.

In conclusion, the SPHERE survey represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of planet formation. By turning dust—the aftermath of cosmic collisions—into a diagnostic tool, astronomers have gained a powerful new window into the dynamic processes that build worlds. These images are more than pictures; they are frozen moments in the billion-year story of solar system evolution, offering a rare and direct glimpse into the hidden workshops where planets are made. They remind us that our own solar system once looked much like these brilliant, dusty rings, setting the stage for the eventual emergence of Earth and, ultimately, life itself.