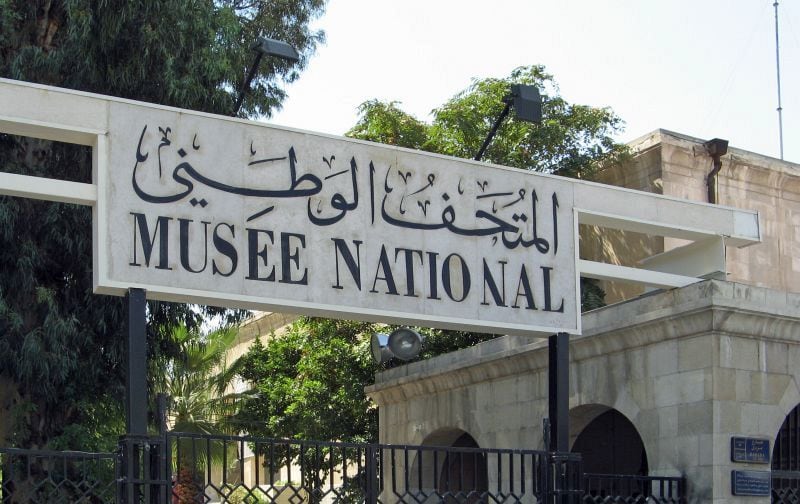

Libya's National Museum Reopens: A Symbol of Hope in a Fractured Nation

The National Museum of Libya in Tripoli has reopened after 14 years of closure due to civil war, marking a significant cultural milestone. The lavish ceremony, featuring fireworks and performances, aimed to celebrate Libya's rich history and foster national unity. Housing Africa's finest collection of classical antiquities, the museum showcases artifacts from Greek, Roman, Ottoman, and Italian occupations. While Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah and cultural leaders hope the institution can help reunify the country's divided east and west, significant political and economic challenges remain. The reopening represents an attempt to reshape Libya's international image and educate a new generation about their heritage.

The ceremonial reopening of the National Museum of Libya in Tripoli represents far more than the return of cultural artifacts to public view. After 14 years of closure triggered by the civil war following Muammar Gaddafi's downfall, this event marks a deliberate attempt to use history as a unifying force in a nation still fractured by political division and economic instability. The museum, housed within the historic Red Castle complex and containing Africa's greatest collection of classical antiquities, now stands as a potential symbol of national identity and resilience. This article explores the significance of the reopening, the treasures within, and the substantial challenges that persist beyond the museum's newly opened doors.

A Lavish Celebration Amid Ongoing Challenges

The reopening ceremony was a spectacle designed to capture both national and international attention. As described in reporting from The Guardian, Martyr's Square in central Tripoli echoed not with militia gunfire but with fireworks and celebrations. The event featured a full Italian orchestra, acrobats, dancers, and dramatic light projections on the fort walls, culminating with a billowing Ottoman sailing ship suspended on wires above the port. Prime Minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah of Libya's UN-recognised Government of National Unity performed the symbolic opening by hammering on the museum's giant wooden doors with a ceremonial stick. This theatrical production, while celebrating Libya's cultural heritage, also served as political theater—an attempt to project an image of stability and renewal to a world that predominantly associates Libya with conflict and chaos.

Treasures of a Crossroads Civilization

Inside the museum's four floors lies a testament to Libya's position as a Mediterranean crossroads. The collection reveals the layers of occupation and influence that have shaped the nation, from Greek and Roman to Ottoman and Italian periods. Among the most significant artifacts are 5,000-year-old mummies from the ancient settlements of Uan Muhuggiag in Libya's deep south, cave paintings comparable to those at Lascaux, tablets inscribed in the Punic alphabet, and countless treasures from the largely unvisited Roman coastal cities of Leptis Magna and Sabratha. These include spellbinding mosaics, friezes, and statues of public figures and deities. Notably absent is Gaddafi's turquoise Volkswagen Beetle, once given pride of place in the collection and one of the few artifacts lost during the uprising. The preservation of these treasures is itself a remarkable story of cultural dedication during conflict.

The Museum as a Unifying Force

Cultural leaders explicitly frame the museum's reopening as an instrument of national reconciliation. Dr. Mustafa Turjman, former head of the department of antiquities, emphasized this point in post-opening discussions, stating that the museum contains "archaeological masterpieces of the whole country" and serves as "a force for unification." The strategic display includes artifacts from both eastern and western regions, allowing Libyans from Tripoli to see statues from Cyrenaica in the east, and eastern visitors to encounter their heritage in the capital. This geographical representation is particularly significant given the country's division between rival governments in east and west since 2014. Turjman further highlighted the museum's educational role in countering the distorted historical narratives of the Gaddafi era, with the first weeks of operation dedicated to school visits aimed at "building the minds" of a new generation.

Persistent Realities Beyond the Museum Walls

Despite the optimism of the reopening ceremony, Libya continues to face profound challenges that complicate any narrative of national renewal. As Prime Minister Dbeibah himself acknowledged, approximately 2.5 million Libyans—roughly one-third of the population—remain on the government payroll, reflecting the country's persistent dependency on oil revenues. Distorted subsidies make petrol cheaper than water, creating lucrative opportunities for smuggling that auditing agencies struggle to prevent. The country ranks near the bottom of international indices for press freedom and corruption, and a Libyan passport offers visa-free travel to almost nowhere. The very night of the museum's reopening saw reported violence, with notorious people smuggler Ahmed al-Dabbashi reportedly shot dead in a gunfight with security forces in Sabratha. These realities underscore the gap between symbolic cultural events and substantive political and economic reform.

Political Stalemate and International Perception

The fundamental political divisions that have plagued Libya since 2014 remain unresolved. Dbeibah, who came to power through a UN-supervised process in 2021, was intended as a transitional figure until nationwide elections could be held. However, he has stated opposition to elections until a constitutional referendum occurs, while political elites in both east and west appear to benefit financially from the ongoing disunity. The UN continues to facilitate "a structured dialogue" aimed at reconciliation ahead of possible elections next year, but progress remains elusive. International perception also presents a significant hurdle. Egyptian comedian Bassem Youssef, an early visitor to the reopened museum, noted that Libya typically appears in global media only during conflicts or crises, creating a distorted image disconnected from daily realities. The museum reopening represents an attempt to reshape this narrative, but as one Libyan official bluntly observed, "Libyans have no clue about politics. Gaddafi prevented that."

Conclusion: Culture as a Foundation for the Future

The reopening of the National Museum of Libya is a significant cultural achievement that demonstrates remarkable preservation efforts during years of conflict. It provides a physical space where Libyans can encounter their shared history beyond recent divisions and offers an alternative lens through which the international community might view the country. However, the museum alone cannot resolve deep-seated political fractures, economic dependencies, or security challenges. Its true success will be measured not only by visitor numbers but by whether it contributes to a broader process of national dialogue and identity formation. As Libya navigates its complex path forward, this repository of ancient treasures may yet play a role in helping citizens imagine a collective future built upon their rich, multifaceted past.