Ancient Crystals Rewrite Earth's Early History: Evidence of a Dynamic Hadean World

New research published in Nature Communications challenges the long-standing 'stagnant lid' hypothesis of early Earth. By analyzing 3.3-billion-year-old melt inclusions in olivine crystals and running advanced geodynamic simulations, an international team of scientists has found compelling evidence that subduction and continental crust formation were active processes during the Hadean Eon. This discovery suggests our planet's tectonic engine started hundreds of millions of years earlier than previously believed, painting a picture of a surprisingly vibrant and geologically active infant Earth.

For decades, the prevailing scientific narrative depicted Earth's infancy as a geologically stagnant period. The Hadean Eon, spanning from 4.6 to 4.0 billion years ago, was thought to be a time when our planet was capped by a rigid, unmoving outer shell—a "stagnant lid." This model suggested that the dynamic plate tectonics and crustal recycling we see today were a much later development. However, a groundbreaking study is now overturning this assumption, revealing that Earth's tectonic engine may have been running far earlier and more intensely than anyone imagined.

The research, conducted by the MEET (Monitoring Earth Evolution through Time) project—a collaboration between geochemists from Grenoble and Madison and geodynamic modelers from the GFZ Helmholtz Centre in Potsdam—combines cutting-edge geochemical analysis with sophisticated computer simulations. Their findings, published in Nature Communications, provide fresh evidence that subduction, the process where one tectonic plate slides beneath another, was already shaping the planet's surface during the Hadean.

The Stagnant Lid Hypothesis: A Long-Held Belief

The stagnant lid hypothesis proposed that after Earth's initial crust solidified around 4.5 billion years ago, the planet remained in a state of minimal surface activity. Heat from the interior was dissipated through mantle convection deep below, but the rigid outer shell did not participate in significant horizontal movement or recycling. In this model, the early Earth lacked the subduction zones and continent-building processes that define modern plate tectonics. This view was largely based on the scarcity of preserved rocks from this ancient era and the extreme conditions following the planet's formation and the moon-forming impact.

New Evidence from Ancient Time Capsules

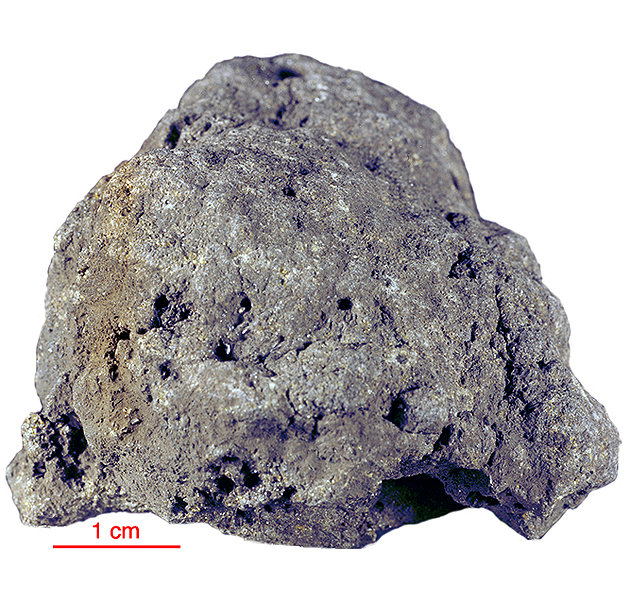

The key to challenging this hypothesis lies in tiny, ancient time capsules: melt inclusions trapped within 3.3-billion-year-old olivine crystals. Researchers from Grenoble analyzed the strontium isotopes and trace elements within these inclusions. Melt inclusions are microscopic pockets of molten material that get sealed inside growing crystals, preserving a pristine chemical snapshot of the magma from which they formed. The geochemical signatures found in these Hadean-era samples told a surprising story.

The chemical patterns indicated that the magmas were not derived from a simple, primitive mantle source. Instead, they showed signs of interaction with older, recycled crustal material. This recycling is a hallmark of subduction, where surface crust is pulled down into the mantle, melts, and then contributes to new magma generation. This finding alone suggested that crustal material was being cycled back into the Earth's interior much earlier than the stagnant lid model would allow.

Geodynamic Simulations Confirm an Active World

To understand how these geochemical patterns could arise, scientists at the GFZ Helmholtz Centre applied advanced geodynamic simulations. These computer models recreate the physical and thermal conditions of the early Earth's interior to test different tectonic scenarios. When the team input parameters consistent with the geochemical data, the simulations robustly supported a model of early, widespread subduction.

The models demonstrated that the heat flow and mantle dynamics of the Hadean Earth were sufficient to drive a form of plate tectonics. This activity would have facilitated not only subduction but also the formation of the first continental crust. Continental crust is thicker, less dense, and more chemically evolved than oceanic crust, and its genesis is intricately linked to subduction processes. The combined evidence suggests that the growth of continents, a defining feature of our planet, began several hundred million years earlier than prior theories proposed.

Implications for Understanding Planetary Evolution

This paradigm shift has profound implications for our understanding of Earth's evolution. An active, subducting Hadean Earth would have had a dramatically different surface environment and heat budget than a stagnant one. Enhanced crustal recycling could have accelerated the cooling of the mantle and influenced the chemistry of the early oceans and atmosphere. The presence of continents would affect erosion, sedimentation, and potentially even the emergence of early habitats.

Furthermore, this research reframes the timeline for when Earth became a dynamically evolving planet. Instead of a prolonged period of quiescence, the Hadean now appears as a crucible of geological activity where the fundamental processes that shape our world today were already in motion. It suggests that plate tectonics, often considered a marker of a mature, habitable planet, may be an inherent feature of Earth's geology that emerged almost immediately after its crust solidified.

Conclusion: A New Chapter in Earth's Story

The discovery that Earth was likely a dynamic, tectonically active world during the Hadean Eon rewrites the first chapter of our planet's history. By marrying precise geochemical analysis of ancient crystals with powerful geodynamic models, scientists have peered further back in time than ever before. The evidence points convincingly away from a stagnant lid and toward a planet that was vigorously recycling its crust and building continents from its earliest days. This not only deepens our knowledge of Earth's past but also provides a new framework for studying the evolution of other rocky planets, asking the compelling question: when did their geological hearts start beating?